U.S. Army Soldiers, assigned to the 6th Squadron, 8th Cavalry Regiment, and the Artificial Intelligence Integration Center, conduct drone test flights and software troubleshooting during Allied Spirit 24 at the Hohenfels Training Area, Joint Multinational Readiness Center, Germany, March 6, 2024. (U.S. Army photo by Micah Wilson)

WASHINGTON — On Monday, as Army acquisition officials laid out their plans for buying and building more AI, one originally high priority was notably absent: a plan to make contractors submit an “AI Bill Of Materials” detailing how their AI was trained and what potential vulnerabilities it might have.

Instead, amid industry outcry, the author of the now-abandoned “AI-BOM” idea said the service will ask for a much less detailed “summary card” meant to feel less intrusive to companies jealously protective of their algorithms and other intellectual property.

“You can think about more like a baseball card that’s got certain stats about the algorithm,” principal deputy assistant secretary Young Bang told reporters Monday. “It’s not as detailed or necessarily as threatening to industry about IP.”

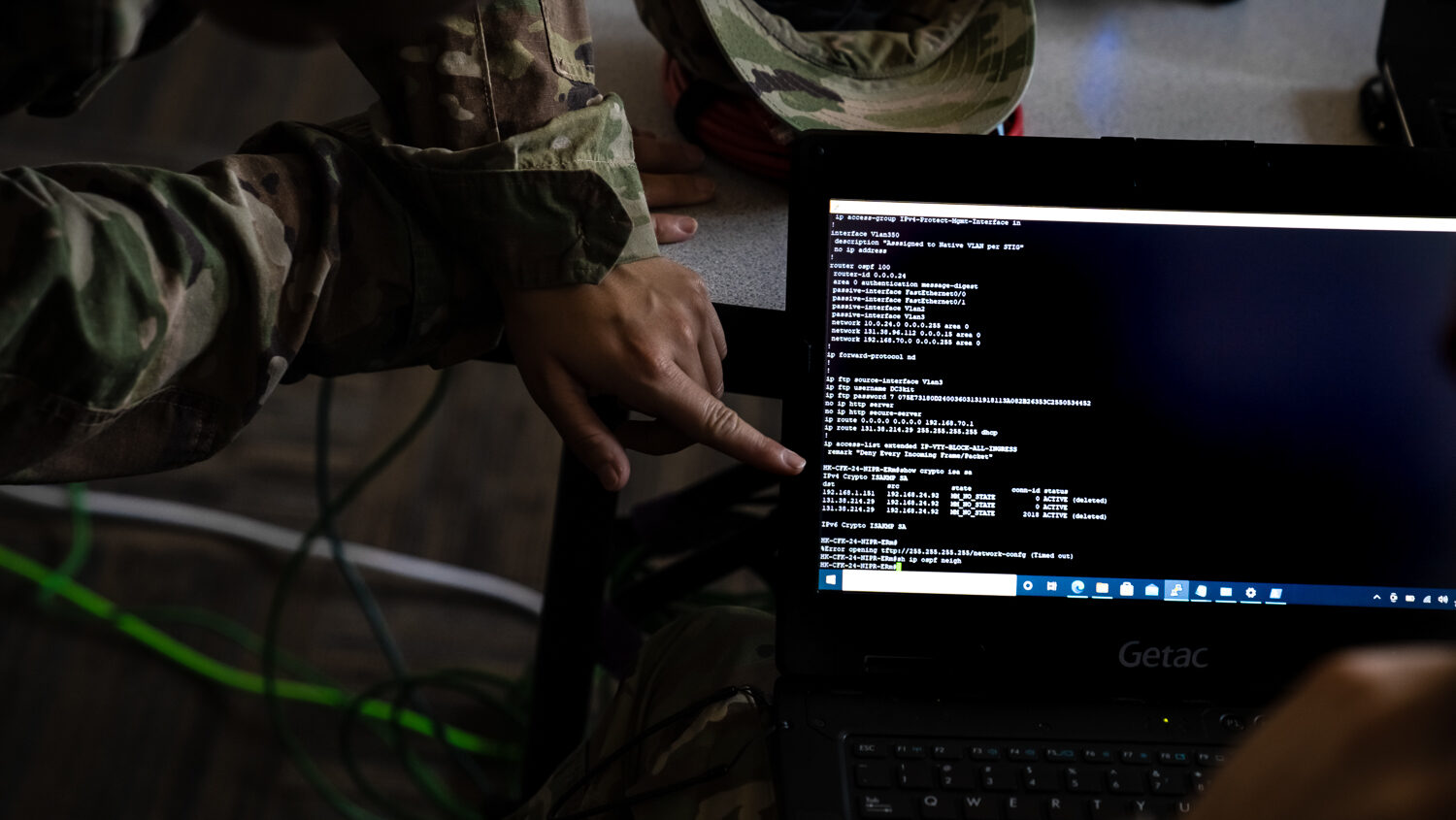

At the same time, however, the Army remains deeply concerned about potential vulnerabilities hidden in AI algorithms, which are born of complex math and then modify themselves over multiple rounds of artificial evolution until they become, in many cases, incomprehensible to humans. A compromised AI could contain “Trojan Horse” malware inserted by a hacker or hostile nation-state, Bang and other officials have warned, or be trained on deliberately distorted, “poisoned” data that makes it lethally out of sync with reality.

RELATED: ‘Poisoned’ data could wreck AIs in wartime, warns Army software acquisition chief

But the Army is keenly aware it can’t take what would, in theory, be the most secure approach and just build all the AI it needs in-house. What it needs, Bang said, is a way to adapt the best AIs from industry, make sure they’re safe, and retrain them as needed for military purposes using sensitive or classified data.

“We think that industry will do algorithm development better than us,” he said, “[but] we may have to do some additional training on data sets that are very specific to the military’s mission sets, that commercial may not have access to.”

So the first and fundamental step is to clean up the service’s own data, from maintenance and personnel records to intelligence and sensor feeds. “The Army has a huge amount of data,” Bang said. “We just have not mobilized or managed it well.”

To fix that, the Army released version 1.0 of a new Unified Data Reference Architecture, which envisions a decentralized “data mesh” of independent but compatible databases, rather than forcing everything into a single all-encompassing “data lake.” UDRA lays out standards for how to manage data that will become mandatory for all service programs, and allowed companies to experiment with it through a recently announced Integration eXchange Lab (IXL).

Once the data is in decent shape, it can flow into a “pipeline” to test, re-train, and develop AI — in a secure environment that the Army itself controls. It’s crucial to keep out “poisoned data sets, adversarial attacks, trojans, and those types of things,” Bang said, “[and] it’s easier to do if you have developed it [the AI] in a controlled, trusted environment that DoD or the Army owns.” It will also be a safe place to bring in algorithms developed outside the Army and retrain or “validate” them, he said.

The effort to build that trusted environment is codenamed Project Linchpin. Just a gleam in the Army’s eye a year ago, the initiative has moved at a lightning pace by the glacial standards of Pentagon acquisition.

“Linchpin happened real fast from concept to program, 12 months,” said Bharat Patel, who’s heading Linchpin work for the Army’s Program Executive Officer for Intelligence, Electronic Warfare, & Sensors (PEO-IEWS). “We’re standing up the program now.”

Last fall, Linchpin awarded two modest contracts — worth a combined maximum of $2 million — to DC insiders Booz Allen Hamilton and commercial titan RedHat to develop AI-vetting tools for “Traceability, Observability, Replaceability, and Consumability” (TORC). It’s also issued four formal Requests For Information that got 500 “data points” in response, met with over 450 companies, and launched a prize competition for small businesses.

Step three, which seems the least refined so far, is to formalize a way to manage AI risks. The idea is “a layered risk reduction or risk framework,” Bang said — “We’re gonna think of a better name.” — that’s now being developed in close consultation with the private sector.

“The Army recognizes that we’re not going to be doing algorithms and all the development and training better than [industry],” Bang said. “They do that extremely well, and so we want to adopt a lot of that” — just safely.

Whatever tools the Army uses to manage risk, however, an AI Bill Of Materials won’t be one of them. The idea derived from an increasingly popular practice called an S-BOM, a Software Bill Of Materials, that lists the potential weak points in a given application, such as the use of open-source code. An AI-BOM starts with an S-BOM but then adds a host of additional requirements to deal with the greater complexity and opacity of AI, such as an outline of what data the algorithm was trained on.

As early as last August, Bang was acknowledging industry concerns about the AI-BOM idea even as he called it “critical”: “We really want industry’s feedback,” he said at the time, “because…y’all can come back and say, ‘well, that’s basically RIP.’”

Indeed, as of now, the AI-BOM seems DOA.

“We’ve been having a lot of engagements with industry and there’s been a lot of feedback from them that …adjusted our thoughts around the AI-BOM,” Bang said Monday. “[Our intent was] not to reverse engineer any IP. It’s really for us to get a better handle on the security risk associated with the algorithms. But we do understand indsutry’s feedback, so we are working more on an AI summary card.”

The Army’s AI push is now in the second month of a 100-day implementation plan approved in May, Bang said, and a longer term 500-day (17-month) plan will come out as a followup this summer.