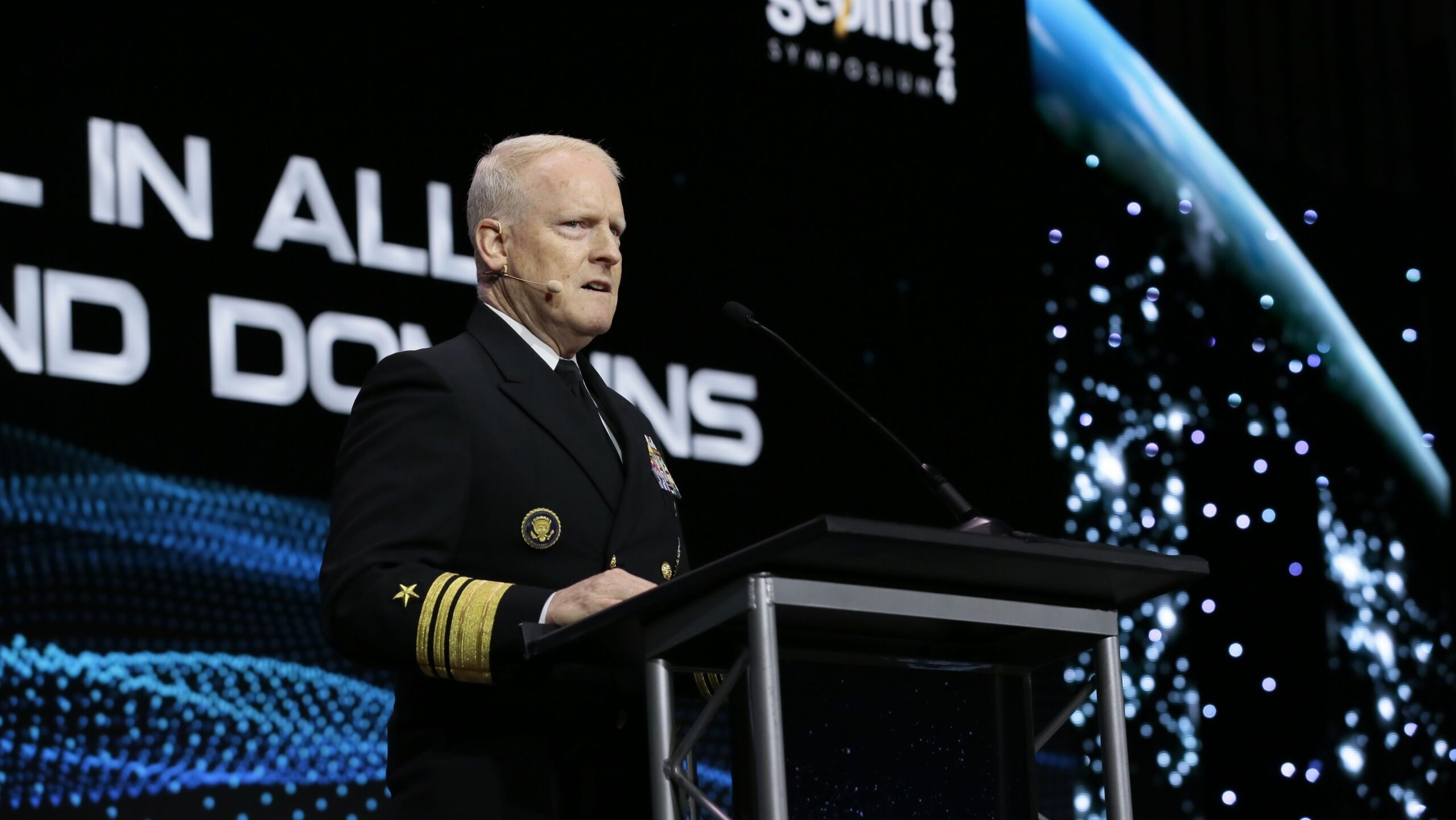

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency head Vice Admiral Frank Whitworth speaks at the 2024 GEOINT conference. (Courtesy GEOINT)

WASHINGTON — Born as an obscure experiment in 2017, the image-processing AI known as Maven has grown into one of the military’s hottest tools for intelligence and targeting, with plans to expand its user base ten-fold. But that growth poses a logistical problem for the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, which took responsibility for running Maven as a formal Pentagon program of record last year.

According to the three-star director of the NGA, Vice Adm. Frank Whitworth, that rising demand for Maven — and Maven’s laudable flexibility in letting users build custom code and even their own AI models — has begun to strain his agency’s resources. Or as he put it, “Success begets challenges.”

Speaking Aug. 29 at a conference hosted by Georgetown University’s Center for Security & Emerging Technology, Whitworth said that, “The number of detections are way up [and] the number of models that we have are way up, but that then drives a computational problem. If you drive that many detections through that many inferences, with the same level of compute that you had in 2017… it starts to slow down. We are already seeing evidence of that.”

As a general rule, text requires less data than imagery, which requires less than video — and Maven was originally built to detect anomalies in full-motion video from Predator drones, whose sheer volume was drowning the military’s cadre of intelligence analysts.

It was “thousands of hours” of full motion video, Bob Work, who launched Maven in his days as Deputy Secretary of Defense, said during the CSET conference. “We would have seven-person teams that worked seven days a week, and they could essentially process 15 percent of the take and the other 85 percent just was thrown out. [So] let’s use machine learning on the Preds to look at all the take, 100 percent.”

As it’s evolved, the Maven AI not only helps the humans by figuring out which intelligence imagery and video is worth their looking at: It also provides a shared digital repository of information that any user — regular or casual — can access at their desk.

So no wonder Maven became so popular with harried staffs struggling to find the needles of actionable intelligence in the ever-growing haystack of digital data.

Whitworth offered an everyday analogy that might be familiar to anyone with a smart phone. “Maybe you accidentally take a picture and it’s high-res, you want to send it to somebody and it chokes?” he asked. “That’s us, every single day.”

RELATED: ‘Who should shoot who?’: INDOPACOM getting ‘combat representative’ JFN this year

“CENTCOM is heavily using MSS [Maven Smart System] in a four-star headquarters with over [20] subordinate headquarters,” said Rear Adm. Liam Hulin, deputy director of operations at US Central Command. “We have about 13,000 MSS accounts,” he told the conference, and of those 13,000, about 2,500 are regular users who log in “at least a few times a week.”

The ability to share information instantly in digital form with every Maven user, Hulin said, stands in stark contrast to “the way we used to do it, [which was] very linear, very slow.”

With hundreds of staff officers and NCOs working on multiple, incompatible systems, traditional staff work required a lot of manual labor to move information from whoever had it to whoever needed it. Staff spent lots of time simply staring at the screen for one system as they manually retyped the relevant data into a different one — a process known sarcastically as “swivel chair integration.”

“You can imagine that there’s a lot of potential for human error…getting every single one of those digits or whatever is being passed accurately,” Hulin said.

By contrast, with Maven and similar systems, one user enters data one time — or the AI automatically ingests it from a sensor without human intervention. “MSS provides us a shared platform for data and artificial intelligence and machine learning capabilities,” he said, “a platform where we use and filter data from 179 different live data feeds.”

NGA got tapped to manage Maven precisely because of its experience managing masses of digital data: As the descendant of the old Defense Mapping Agency, it handles satellite imagery detailing every place of interest on the earth, often accompanied by detailed textual commentary from expert intelligence analysis.

“We move and store in the IC [Intelligence Community] cloud….more data, ones and zeroes, than any other agency,” Whitworth said. “I won’t tell you how much, but it’s a lot.”

But even NGA has to update its practices for Maven and the age of AI. Besides the sheer demand for computing power, Whitworth said, NGA’s highly skilled human analysts have to adapt to the additional demands to label data to make it easier for AI to ingest — a system of cataloging that’s not the same as NGA’s established practices.

“Data labeling is a little bit different than the ordinary process of building what we call ‘structured observations,’” Whitworth explained. “If I’m going to require my workforce to take 15 percent of your day and stop what you’re doing with structured observations and do some data labeling, they’re going to have a problem.”

While Whitworth didn’t come out and say explicitly that NGA needed a bigger budget to meet the rising demand, he came extremely close. “[It’s] a potential resource issue,” he told the conference. “We have the same amount of people, the same amount of compute, we’re going to ask them to do data labeling with more detections.

“I’m going to continue, frankly, educating and collaborating and ensuring people know that this is what we’re up to,” Whitworth said.