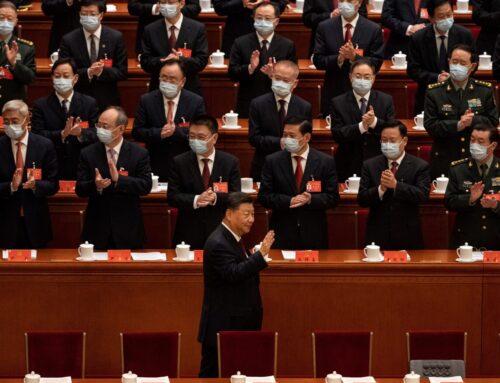

Soldiers try to enter the National Assembly building in Seoul on December 4 2024, after South Korea President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law. South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol on December 3 declared martial law, accusing the opposition of being “anti-state forces” and saying he was acting to protect the country from “threats” posed by the North. (Photo by JUNG YEON-JE/AFP via Getty Images)

SYDNEY — South Korea appears to have survived a brief, stunning attempt by its president to impose martial law, but the aftermath may lead to lasting damage in its relations with allies and partners, including the US, analysts told Breaking Defense.

President Yoon Suk Yeol had based his foreign policy around being tougher on North Korea, a tighter embrace of the United States and, perhaps most controversially inside South Korea, pushing for closer defense relations with Japan, including by restarting a major intelligence sharing agreement with Tokyo.

His fall — which seems inevitable 24 hours after his martial law declaration, with his defense minister offering to resign over the plan and an impeachment process underway — will have “profound” effects on those foreign policy goals, according to Chun In-bum, a former deputy commander of South Korea’s First Army.

“The entire ordeal lasted only six hours, yet its implications are profound. It was bizarre, embarrassing, and politically damaging for the Yoon administration. The short-lived declaration of martial law raises significant questions about the president’s judgment, the advice he received, and the decision-making process within the government,” Chun wrote in an email to Breaking Defense, adding that the “political fallout will be severe and long-lasting.”

The extent of that fallout, predicted Euan Graham, will be global. “If Yoon’s impeached and the progressives regain power then I think the outlook for bilateral relations with Japan and the US trilateral will darken,” Graham, a regional expert with IISS, told Breaking Defense.

However, don’t expect immediate changes.

“Yoon is unlikely to resign but there is already enormous public outcry and bilateral political support for his impeachment. The National Assembly already has impeachment bills moving, and they will likely pass quickly,” said Jenny Town, an expert on the Korean peninsula at Washington’s Stimson Center. “Yoon will be removed from duty and Prime Minister Han [Duck-soo] will assume interim presidential duties.”

Under South Korean law, Parliament may impeach the president. If it does and it is upheld by a Constitutional Court then a successor must be elected within 60 days. Yoon would serve in the interim for at least part of that time.

“It should be noted that Lee Jae-myung, the most prominent of the opposition leaders, is currently ineligible to run for president due to his own legal problems,” Town wrote in an email to Breaking Defense, raising questions about who will run to replace Yoon.

“The incident leaves lingering doubts about the future of the nation’s political climate and the ability of its leadership to navigate complex challenges. It will serve as a sobering case study in the delicate balance of power, the risks of executive overreach, and the resilience required to uphold democratic principles,” Chun wrote.

Impact On Japan

Once Yoon is forced out, there may be a retrenchment against tighter relations with Japan, analysts said. Yoon’s desire to tighten bonds with Tokyo, while championed in Washington by national security officials who always view Japan and South Korea as natural allies, has never been popular domestically, where the wounds from World War II remain raw for the public.

Notably, the impeachment resolution introduced in the National Assembly specifically calls out Yoon’s approach to Japan as part of the reason he should be forced out, including accusations he “adhered to a peculiar Japan-centric foreign policy,” per a translation.

Chun was blunt, saying that if Yoon goes and the more liberal opposition wins, “Japan-Korea relations will go down the drain.”

One area where a new president may reverse gains made with Japan is on the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), an intelligence-sharing system originally set up in 2016, paused in 2019, and then restarted by Yoon and his Japanese counterpart, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, in 2023.

Both Chun and Leonid Petrov, a Korean expert at the Australian National University in Canberra, said that freezing participation in GSOMIA would be an easy anti-Japanese move for the next government to make, with Petrov adding that Yoon’s actions might raise serious concerns among the Japanese about the stability of South Korea’s leadership.

Yoon Suk Yeol, South Korea’s president, left, and Fumio Kishida, Japan’s prime minister, shake hands ahead of a summit meeting at the prime minister’s official residence on March 16, 2023 in Tokyo, Japan. (Kiyoshi Ota – Pool/Getty Images)

As for the bedrock relationship for South Korea, that with the United States, Town said much will ride on who South Korea elects as their next leader — who will regardless likely start on a back foot with President-elect Donald Trump.

“This reminds me a bit of 2017 in the sense that no matter who the next president of South Korea is, they will be late to the game with Trump. South Korean leadership was in flux the first time Trump took office, meaning others had the advantage of making a strong first impression,” Town wrote. “While there was some speculation that Trump and Yoon would get along well, the opportunity to get in early and make a strong first impression is gone.”

How much all of that will change will depend a great deal on how Trump, who appears skeptical of alliances in general, actually approaches the one with South Korea and the one with Japan, Town said. That may drive South Korea to move “back toward greater strategic ambiguity in balancing its relations between the US and China.”

“If Trump takes aim at [South] Korea for more host nation support payments, then obviously that spells trouble,” Graham noted. “The Korean president is not the only variable” in the Washington-Seoul relationship.

How Will North Korea Respond?

Will all this uncertainty lead to saber-rattling or more dangerous moves by North Korea? Town doesn’t think so.

“If [former President] Park Guen-hye’s impeachment [in 2016] is any indication of how Pyongyang may be assessing the situation, they are unlikely to do anything overtly provocative toward South Korea in the coming weeks or months to disrupt the process. They will likely get in a few rhetorical jabs at Yoon on his way out, but otherwise see how the situation plays out,” Town said.

She added that Pyongyang is deeply engaged in helping Russia in Ukraine, and “those efforts will not be put on hold because of what’s happening in the South.”

Petrov is also skeptical North Korea will look to make a move, even though, he said, Pyongyang will likely interpret the South Korean military’s unwillingness to use force against civilians during the six-hour crisis as a sign of weakness.

Instead, Petrov said, expect North Korea to use the political and military disorder shown in the last two days for propaganda purposes and let it speak for itself.

For its part the US has been quick to stress that peace and order is maintained.

“The United States has watched closely developments over the last 24 hours in the Republic of Korea,” said Antony Blinken, US Secretary of State in a statement on Tuesday. “We welcome President Yoon’s statement that he would rescind the order declaring emergency martial law in accordance with the ROK Constitution, after the National Assembly’s unanimous vote to reject the declaration. We continue to expect political disagreements to be resolved peacefully and in accordance with the rule of law. We reaffirm our support for the people of Korea and the U.S.-ROK alliance based on shared principles of democracy and the rule of law.”

Aaron Mehta in Washington contributed to this report.