The outcome of the recent presidential election sets the stage for the United States to reassess its military and diplomatic goals. By crafting the appropriate national security strategy, the nation avoids costly policy errors and sets the stage for proper long-term investment in its defense capabilities. The upcoming budget review should be about defining the threat, understanding the needed force to defeat it and ensuring that the industrial base is properly incentivized and capable of equipping the armed services. In an unpredictable world a strong and innovative military is essential to protect the United States and its economic interests.

The outcome of the recent presidential election sets the stage for the United States to reassess its military and diplomatic goals. By crafting the appropriate national security strategy, the nation avoids costly policy errors and sets the stage for proper long-term investment in its defense capabilities. The upcoming budget review should be about defining the threat, understanding the needed force to defeat it and ensuring that the industrial base is properly incentivized and capable of equipping the armed services. In an unpredictable world a strong and innovative military is essential to protect the United States and its economic interests.

At $850 billion, the planned budget for FY 2025 is probably below what would be ideal, but at this level it is modest insurance relative to the resources the military protects. Government outlays for defense are just under 3% of the $28.3 trillion U.S. GDP. If we go back 10 years, defense spending was about 3.3% of GDP. Three decades ago, in 1993 when the Cold War ended, military spending was under $280 billion, or 4.1% of GDP. So, the cost to defend our nation is declining as a percentage of economic output. Looking at it another way, the total active-duty force is down from 1.8 million at the end of FY1993 to just under 1.4 million today. The DoD’s civilian workforce is 10% smaller at around 800 thousand. The U.S. has a stronger defense with fewer soldiers. Could we find ways to be more efficient, probably. Is there non-essential work being performed by the civilian workforce; of course.

So, here are some thoughts on change. For the annual budget, the Pentagon should spend more time on the outliers, with a lighter touch on the recurring items, reducing bureaucratic costs. Find the levers in procurement laws that can speed up reviews and enhance oversight. Select practices that cut paperwork on recurring buys. Operating and Maintenance is 40% of the DoD budget; invest to reduce recurring costs. Craft better proposals and raise the hurdle for bid protests. Deliver the budget on time. Delay costs money and harms readiness. It’s in the national interest for all parties to work together.

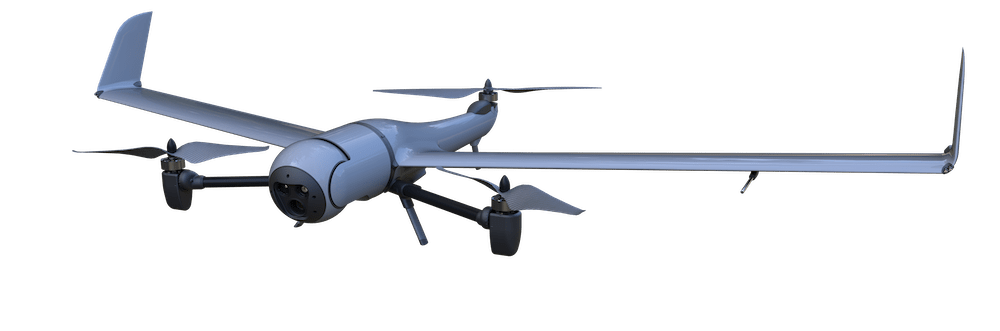

The ability to deliver more for proportionally less has been driven by forward-thinking leaders who recognize that strategy drives outcomes, not folks with green eyeshades. The adversary gets a vote too, so the Department of Defense needs to have a competitive fighting force while it evolves and deploys new technologies to defeat new threats. For example, it needs to kill thousand-dollar drones with directed energy systems or small projectiles, not million dollar missiles.

A compelling strategic framework is Defense Secretary Rumsfeld’s vision set out in the May/June 2002 issue of Foreign Affairs. He argued that our security challenges are not as predictable as those of the Cold War. Given the advances and spread of technology, his argument is as relevant today as when he wrote it. His prescience is notable. He cited the need for more unmanned weapons, long-range systems and improved information networks. Those ideas are a reality with the B-21 bomber, the unmanned MQ-25 drone, and significant funding for software-defined radios and cyberspace activities.

With the end of the Cold War, many companies left the industry to others who had a vision of how to operate in a more constrained and volatile environment. Successful companies cut overhead, consolidated factories to match demand and transformed production lines to meet the next need. As an example, demand for air-to-air missiles declined, but the requirement for long-range strike missiles rose.

Today, the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile and its sister the Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile are built on the same production line, share costs and are highly effective weapons. Aerial dog fights are down, but ground or ship-based targets have proliferated. These industry leaders innovate and have the capability to do more.

In addition to restructuring their industrial footprint, the industry took other actions to deliver economic value to the Pentagon and shareholders. Multi-year contracting was employed with efficiencies shared with the Pentagon. Competitive development programs were crafted to balance risk and innovation.

In recent years, the Army had Night Court, a process that scrapped lower priority programs to free up about $35 billion to fund its modernization. The Pentagon has pursued partners in Silicon Valley, and it created the Defense Innovation Unit in 2015 to help the U.S. military make faster use of commercial technologies.

There are many lessons from the war in Ukraine; funding and industry response to battlefield needs were faster than a budget cycle. In a related example, contracting terms could be further revised to pay for war reserve capacity. Future contracts should have a war-related surge clause. Solely employing unit costs as the metric for value misses the need for long-term preparedness.

Finally, Congress, with its control of the nation’s purse strings, needs to support a concrete plan that delivers recurring and verifiable value to the public and to the Pentagon’s suppliers.

Howard A. Rubel was a highly regarded sellside equity analyst for nearly 40 years, actively engaging with industry participants as it was undergoing a major transformation. Beginning in 2018, he broadened his industry experience by serving for six years as V.P. of Investor Relations for General Dynamics.