Bell’s V-280 Valor is the US Army’s Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft. (Bell)

With the Future Long Range Attack Aircraft (FLRAA), the Army is introducing a new developmental aircraft type for the first time in decades. That creates myriad challenges for not only the prime contractor but for individual supply chains associated with the aircraft, the powerplants, and the digital backbone.

Breaking Defense discussed the role of the industrial base in Future Vertical Lift with FLRAA Project Manager Col. Jeffrey Poquette.

Breaking Defense: Before we get into the industrial base discussion, where does the FLRAA program stand at this moment in time?

Jeffrey Poquette: FLRAA had its Milestone B decision back in the summer, which kicked off a lengthy phase in the acquisition program called EMD, Engineering and Manufacturing Development. Over the next year we’re focused on getting to the critical design of the aircraft – all the exact things that Bell will use to produce the aircraft prototypes that we’ll then use for tests.

All of that will inform a Milestone C decision in 2028, which is to make a decision on production of actual fieldable aircraft.

What are the supply chain and logistical challenges of introducing a new aircraft type like a VTOL?

The last developmental rotorcraft [in the Army was] about 40 or so years ago. So, yes, there are challenges and at the forefront are the industrial base and supply chain risk. This was highlighted during COVID, how fragile the supply chains are – everything from cars to electronics. On the defense side, we’ve seen it with ammunition and now with aircraft, which is a very complex weapon system with a lot of components.

I wouldn’t say that there are unique challenges particular to a tiltrotor. A tiltrotor is a kind of rotorcraft, a helicopter is a kind of rotorcraft, and both of them have complex supply chains that we have to manage carefully. Ensuring a resilient supply chain has been at the forefront of this program for many years now. We’ve stood up a supply chain risk management team that looks at everything from the raw materials, to finished products and subcomponents [at] the lowest level in the supply chain.

As we work with industry to ensure we have that resilient supply chain, one of the ways that we control that is through something called a ‘consent to subcontract’, which is relatively new. [For example,] when Bell wants to subcontract with a supplier, they have to prove out a number of things, and one is supply chain resilience and risk level.

My team then assesses it and before I sign off on that consent, we take a look at supply chain risk management. All programs have supply chain risks, and we’ve learned from that over the years and leaned forward early in the program to ensure that we have the mechanisms in place to carefully and appropriately manage a supply chain together with our industry partners.

Army Col Jeffrey Poquette is the Army’s FLRAA program manager.

What are some of the key capabilities that you’re looking for in this consent-to-subcontract process? What does industry need to show you?

Hypothetically, if there was a material that was a particularly rare resource or difficult to obtain, we would manage that carefully, ensuring that there’s multiple sources of supply. We also do Manufacturing Readiness Assessments, or MRAs, which we’ve done since before our Preliminary Design Review.

When we look to industry’s role, they know their supply chain best. Typically, the Department of Defense has always been reliant on industry to provide that information.

When I go out to industry engagements and meet with suppliers, one of the first things I ask them, besides the ability to protect the program, is how is their supply chain, how have they been weathering the supply chain challenges of COVID? Have they recovered from that? What have they done to multiple source their own suppliers, tiers 3 and 4 down into the supply chain? Do they have risky raw materials that they need to source from overseas, that maybe the United States doesn’t have a large access to?

We take a hard look at that, and then when appropriate, we suggest to Bell that if we see a particularly risky supply chain then perhaps we don’t provide the consent to subcontract until they remedy or mitigate that risk.

How are you working now to prepare the industrial base for the long-term production of FLRAA? What is its role over the next few years in the run up to LRIP?

There’s two kinds of groups of companies right now when it comes to FLRAA. [The first is] the group that’s already part of Team FLRAA, the ones that Bell has selected and that the government has approved to be a part of FLRAA.

The [others] are the ones who want to become part of the FLRAA ecosystem. How do they do that, what should they be getting after? Those are the questions they ask me.

One of the ways that people will be able to become part of FLRAA relatively easily should they provide a great product that’s competitive in price and brings great capability, is [through] our Modular Open Systems Approach. In the past, we relied heavily on OEMs to integrate new capabilities; we would have to always go back to the OEM or the aircraft provider. What our Modular Open Systems Approach does is foster innovation, competition, price competition, and it allows us to focus on what matters.

As a PM, I do not want to be spending a lot of money to integrate a great capability. I want to spend money on the great capability itself. I want the juices flowing out there in industry, and for the industrial base to be competing on the things that will matter to us.

I’ll give you some broad categories of technologies that we look to [such as] things that reduce weight, or have lower power requirements. The lighter you can get the aircraft, the more performance you get out of it.

Dual-purpose technology that might do two things rather than one unique thing is very important to us. Being able to collapse capability into a chassis and have card-based solutions, so rather than eight boxes each doing a different thing, we have one box with eight cards that can provide the capability. That speaks to SWaP. Aviation survivability is always something we’re interested in.

That’s all enabled by our digital backbone, which are the physical components of the aircraft that allow other capabilities to integrate into. What we want to do is open the door for innovation. Industry should know that once they get on the platform they’re not locked in, because that same competitive spirit and the MOSA aspect of the aircraft will allow us to move on from them, maybe three or four years later when something better comes along.

How do you balance the use of new developmental technologies on FLRAA versus mature technologies with high TRL?

One of the approaches with FLRAA was to focus on the aircraft itself. You may have heard me say, ‘twice as far, twice as fast’. That’s new technology we’re trying to mature, and then we want to mature MOSA. But everything else right now in this early iteration of FLRAA will be high-maturity mission systems that you see today on the Apache, the Black Hawk, and the Chinook.

It’s an iterative approach. In the past, new aircraft tried to be everything all at once to everyone, and had a lot of new technology on the aircraft. What that does is inject risk into the program, and the potential for delays and expense.

By focusing on the aircraft and MOSA, we give ourselves an opportunity to succeed with less risk, and then look to the future to take advantage of MOSA and those technology categories I’ve mentioned.

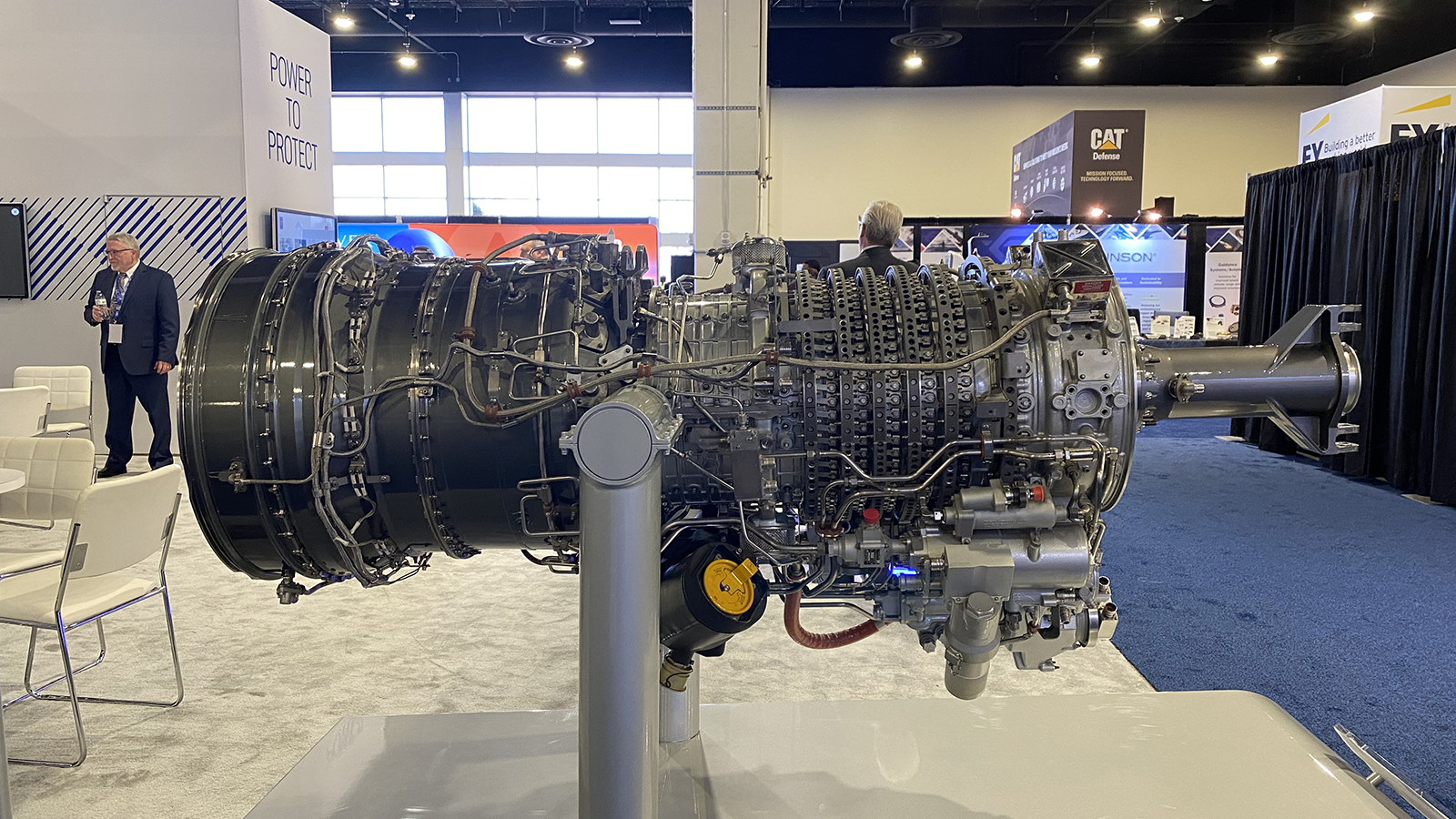

A model of the Rolls-Royce AE1107 engine on the Sea Air Space 2023 show floor. The engine is the powerplant for the MV-22, CV-22 and CMV-22 Osprey variants, as well as the engine for the Army’s V-280 FLRAA tiltrotor that attained Milestone B earlier this year. (Aaron Mehta / Breaking Defense)

There’s also going to be an engine supply chain to build the Rolls-Royce powerplant. What are the specific industrial base challenges associated with the engine?

One of the benefits of FLRAA is that because it’s a contractor-furnished powerplant, Bell has chosen an engine that exists already. There will be changes. The 1107F is the engine being developed for FLRAA, but there is a family of 1107 engines out there. The Charlie is on the V-22, and there’s a version on C-130 and other aircraft. The good news is it’s a mature supply chain, and although there will be changes it’s not like we’re developing a new engine for this aircraft.

You might remember, the FARA program was developing a new engine. The Improved Turbine Engine was being developed in parallel with the aircraft. In this case, we have a mature supply chain when it comes to the powerplant.

The FLRAA digital backbone is also a key element of the program. Tell us about that industrial base?

The digital backbone is a combination of hardware and software, and forms a subsystem that’s integrated into the aircraft that enables the networking across the aircraft. I call it the nervous system of the aircraft that allows the relay of information.

A lot of the components of that are not specialized. They’re switches and routers and things that move information across cables. It’s not a unique supply chain, or particularly specialized.

It’s really in the software – the software that they developed to enable the relay of information so that the flight-critical data gets priority.

In the past, everything was point-to-point. Things that were critical had a box and a wire that took up size, weight, and power. If you can do all that relay of information on a single network, in this case the digital backbone, you get after that SWaP issue and don’t have all these computers on board.

In my estimation, it’s the software that’s the special sauce, so to speak, in the digital backbone.

The Army wants more control over the intellectual property to prevent vendor lock and to modernize capabilities over time. What systems on FLRAA do you expect to have greater IP control over?

During the competition, we were very deliberate in the development of our IP strategy. Historically, one of two things happens. We never know exactly what we need and when we’re going to need it. We would ask for too little, not have what we need 10 years down the road, [and] realize we don’t have access to that IP. Then you’ve got to get it, which may be difficult, expensive, or even impossible.

The other end of the spectrum is you don’t know what you need, but you don’t want to take the risk of not having it. So you ask for it all, but end up getting a lot of stuff you don’t need that you pay for.

How do you get that minimum amount to do exactly what you need to do? IP for the Army is focused around logistics functions like training, maintaining, sustaining. The Army is very focused on field-type maintenance, and even at the depot level we do a lot.

We have the heritage of wanting to be able to do that without reliance on contractor support, especially where the Army operates deep in areas that are considered hazardous. Unlike Afghanistan and Iraq where we had relative sanctuary on bases throughout those countries and it was easy to bring contractors in there, it may not be easy to do in the future. We’ve got to be able to maintain it and sustain it.

So how did we do that? Rather than ask for specific IP, we presented to the contractor what it is we wanted to do. We did that in hundreds of use cases. We need to be able to develop training materials and manuals, we need to be able to change them when it’s time to change them. We need to be able to instruct and train on how to do maintenance. We know what we want to do, we just don’t know what we need to do it. Who better to know what we need than the contractors themselves, whether it’s Bell or the OEM of particular components?

What we did was incentivize the contractors during competition to provide the most that they could in order to meet those use cases. Once we had a winner in the competition, we signed Bell up to provide all that intellectual property.

You asked about controlling the IP. We’re more interested in access to the IP that we need so that we can do the things we need to do. That’s a key takeaway. Because of that, we’ve been designated [as a] Department of Defense IP Pathfinder.

Broadly, industry agrees that they want the Army to have what we need in order to execute the use cases. But the specifics of that takes a lot of hard work, and we [recently] spent a week with our industrial base talking through that, getting to the right words and agreements where they can feel comfortable that what they provide us to do those things we need to do will not put them at a competitive disadvantage in the future.

Our strategy does just that. We’ve gotten a lot of support from our higher headquarters at ASA (ALT) in the Pentagon. I, my deputy, and my logistics division chief spend a lot of time talking about this very subject, and trying to propagate the approach, which I think is novel and effective in getting access to the appropriate amount of IP while still protecting the creators of that IP.