A view of the U.S. Starfish Prime high-altitude nuclear test taken at Maui Station in Hawaii on July 9. 1962. A view of the U.S. Starfish Prime high-altitude nuclear test taken at Maui Station in Hawaii on July 9. 1962. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

WASHINGTON — The Biden administration is taking to the bully pulpit to voice its conviction that Russia is moving to put a nuclear weapon in space designed to destroy satellites — with a senior State Department official for the first time today explaining that the concern is centered on a specific satellite development Moscow claims is aimed at testing electronics.

“The United States is extremely concerned that Russia may be considering the incorporation of nuclear weapons into its counterspace programs, based on information deemed credible,” Mallory Stewart, assistant secretary for the Bureau of Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability, told the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“The United States has been aware of Russia’s pursuit of this sort of capability dating back years, but only recently have we been able to make a more precise assessment of their progress. Russia has publicly claimed that their satellite is for scientific purposes,” she said.

“However, the orbit is in a region not used by any other spacecraft — that in itself was somewhat unusual. And the orbit is in a region of higher radiation than normal lower Earth orbits, but not high enough of a radiation environment to allow accelerated testing of electronics as Russia has described the purpose to be,” Stewart elaborated.

RELATED: From Russia with nukes? Sifting facts from speculation about space weapon threat

Like other Biden administration officials before her, Stewart rushed to assure listeners that this “is not an active capability that has already been deployed. Although Russia’s pursuit of this capability is deeply troubling, there’s no imminent threat.”

And similarly to those officials, she would not characterize the potential timeframe in which Moscow might be able to deploy that capability.

Russia’s April 24 veto of a UN Security Council resolution to reaffirm the 1967 Outer Space Treaty’s bar on weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in space crafted by the US and Japan seemly has set the Biden administration free with its criticism of the alleged plan. (Russian President Vladimir Putin has issued a blanket denial of any such intent.)

The US-Japan resolution marked the first time the issue of outer space security has been put before the UNSC — although debate has been ongoing for decades in other UN bodies.

White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on April 25 issued a statement confirming the Biden administration’s belief that Russia is pursuing a nuclear ASAT, and raising questions about Moscow’s rationale for its veto.

And on May 1, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy John Plumb in written testimony to the House Armed Services Committee doubled down on the accusation, which in fact was first leaked by Rep. Mike Turner, R-Ohio, the chair of the House Intelligence Committee.

“Russia is also developing a concerning anti-satellite capability related to a new satellite carrying a nuclear device that Russia is developing. This capability could pose a threat to all satellites operated by countries and companies around the globe, as well as to the vital communications, scientific, meteorological, agricultural, commercial, and national security services we all depend upon,” Plumb wrote.

Stewart echoed Plumb’s statements at the HASC hearing that while the effects of a nuclear blast in space would depend on a number of factors — including the precise orbit of the detonation and the size of the bomb — there could be long-standing damage down to the global space commons from such a weapon.

“Our analysts assess that detonation in a particular placement in orbit of a magnitude and location would render lower Earth orbit unusable for a certain amount of time,” she told CSIS.

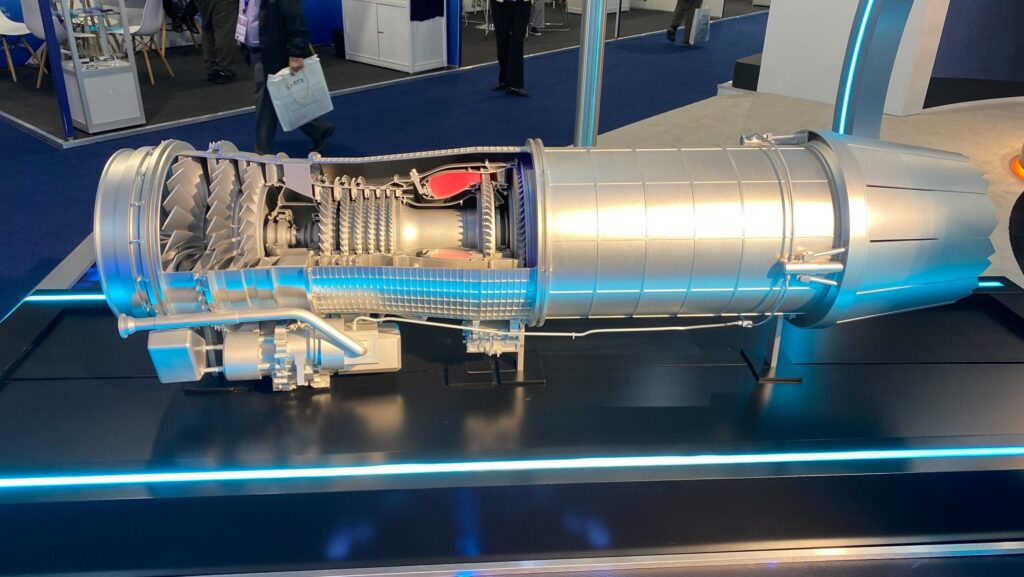

Nuclear weapons have been detonated in space before, by both the Soviet Union and the US during the early days of the Cold War. The largest was done by the US in 1962: After a series of failed tests, the United States conducted the Starfish Prime experiment, setting off a 1.45 megaton nuke at an altitude of about 450 kilometers (about 280 miles) above sea level.

The blast created an electro-magnetic pulse and lingering radiation belts that ultimately killed eight of the 24 satellites that were then on orbit, including one owned by the United Kingdom, according to a 2022 report by the American Physical Society.

Victoria Samson, director of the Secure World Foundation’s Washington Office, said that much remains unclear even as small details are being put out in dribs and drabs.

“There are still a lot of unanswered questions and that is probably due to the fact that so much of this depends on intel-gathering or is still amorphous. One thing that seems to be clear is that the US seems to think that the weapon (and it is clearly thought to be a WMD) would be placed on LEO,” she told Breaking Defense.

Stewart said that the US government is continuing to press the issue at the United Nations and other international forums. Most immediately, she noted, Russia’s Security Council veto will be discussed in the UN General Assembly on May 6 — a forum open to all UN member nations.

Samson explained that the May 6 meeting “will be a veto initiative debate on the vetoed US/Japan resolution” — based on an April 2023 UN resolution that allows such a debate 10 days after a veto. That resolution, she explained, “tracks back to concerns last year that the UNSC veto was being unfairly wielded.”

Further, Stewart said, the Biden administration is “continuing to engage bilaterally and multilaterally and to use all the diplomatic tools in the context … of the CD — the Conference on Disarmament — the UN First Committee and other diplomatic forums in which these exact issues are being discussed. So, we hope to continue to have these conversations there.”

![The sights from the 2024 Farnborough Airshow [PHOTOS]](https://centurionpartnersgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IMG_8722-scaled-e1721930652747-1024x577-hZjwVb-500x383.jpeg)