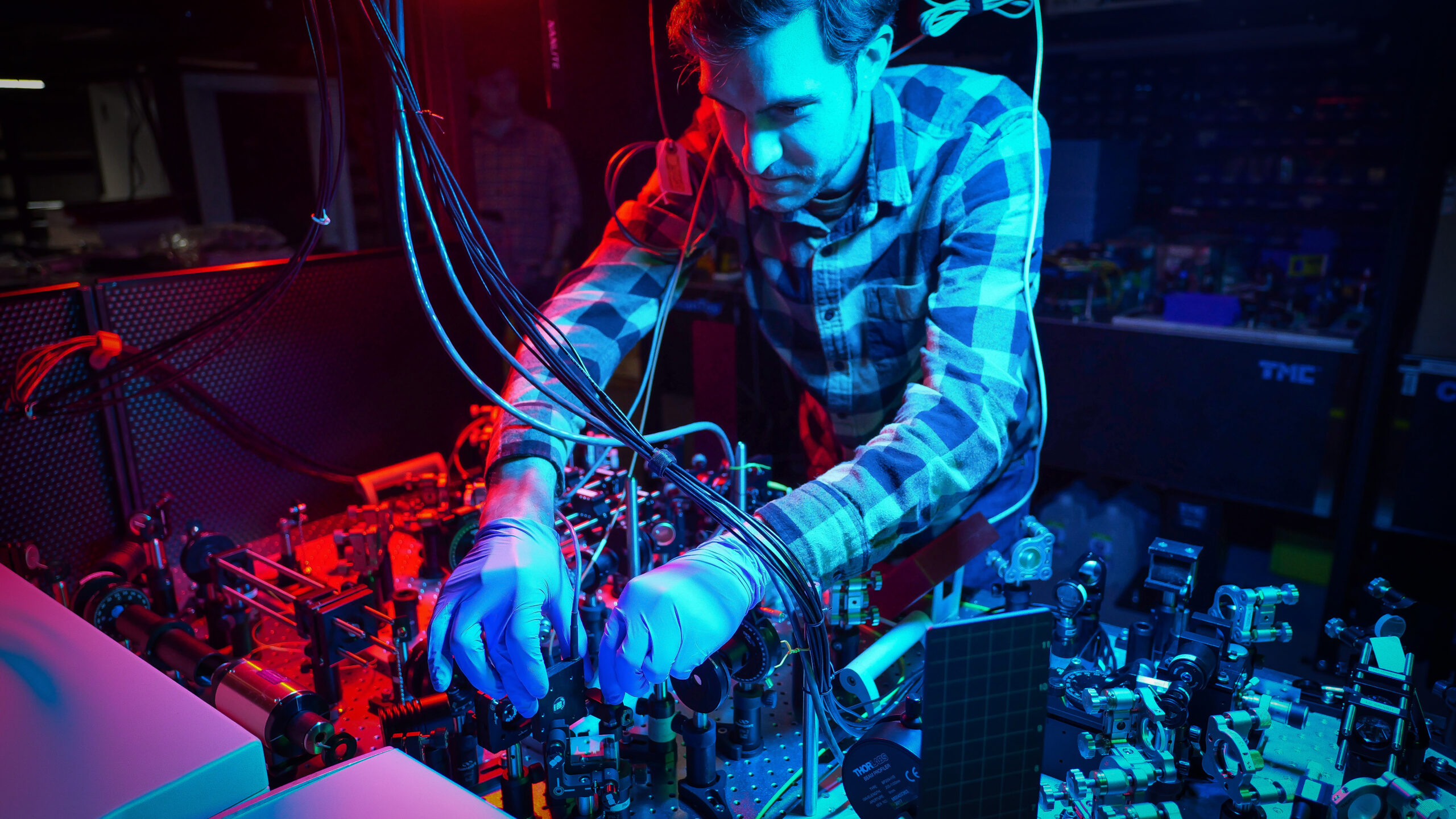

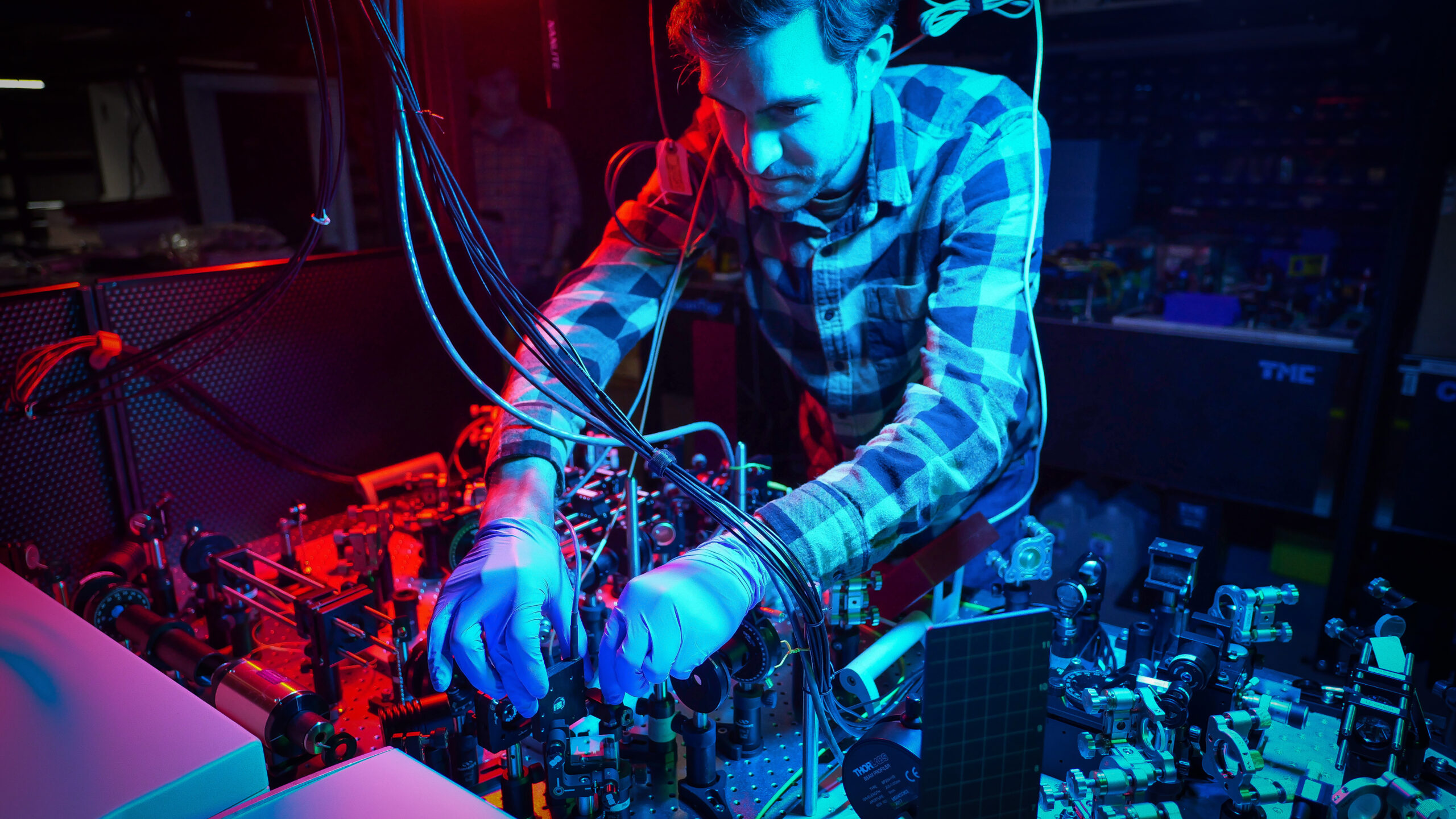

Air Force Research Laboratory scientists work on various technical platforms to accelerate quantum research and development of connected ultra-secure quantum communication to provide the best benefits to the Department of the Air Force and the warfighter. (US Air Force photo / Keith Lewis)

WASHINGTON — While quantum computing hogs the hype — and the venture capital — military officers and officials increasingly see the biggest near-term possibilities in quantum sensors. Measuring the same kind of microscopic motion as atomic clocks, quantum magnetometers, gravitometers and more could help frontline forces navigate when GPS is jammed or hunt targets without conventional radar and sonar. But first, they have to work reliably outside the lab.

To make that happen, the Pentagon’s outreach arm to Silicon Valley, the California-based Defense Innovation Unit, has just announced a slew of contracts to field test a dozen different quantum sensing systems. (This is similar to but separate from an ongoing DARPA effort to harden quantum sensors). The 18 vendors announced so far — another one or two might yet emerge from ongoing contract talks — include defense titans Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, established military-and-commercial players Honeywell and Leidos, upstart Anduril and a long list of smaller companies, many of them providing a single critical component to a larger team.

“It’s a good mixture of traditional primes, non-traditional defense, as well as emerging and startups and small business,” said Air Force Lt. Col. Nick Estep, DIU’s portfolio manager for emerging capabilities, in an exclusive interview with Breaking Defense. Using its preferred Commercial Solutions Opening process, DIU issued its initial solicitation just 10 months ago in May, sorted through more than 70 proposals, and got the most promising firms on contract, with many already at work.

“I would say roughly a dozen meaningful field tests are going to occur by the end of the fiscal year. … Some of these will be on small autonomous systems; some will be on manned aircraft; some will be ground tests.”

DIU calls its project Transition of Quantum Sensors (TQS) because it’s working closely with DoD Quantum Tech Director John Burke, the Air Force, Navy and potential military users with the intention to identify mature technology, ruggedize it, test it, fix the inevitable glitches and hand it over to procurement programs for real-world operational deployment.

“I’m a scientist by trade,” said Estep, an electrical engineering PhD who’s worked in both academia and the National Reconnaissance Office. “Our inclination is to optimize for as long as possible and build the best sensor you can possibly build in your lab. … It may have had some amazing performance for like five seconds in the lab when everyone stopped and held their breath, [but for the military] you can’t deploy with five grad students and expect ideal thermal, moisture, and environmental conditions.”

Traditional Pentagon procurement tends to perfect technology in ideal conditions, only to discover practical problems when it first goes to the field. Far better, the DIU team believes, to put an 80 percent solution in the field ASAP and find those flaws, and fix them, early on.

For any given quantum sensor, Estep explained, “we need to ruggedize it, integrate it with the controlling subsystems into a meaningful package, and answer: ‘How would we deploy it? How are we going to show functionality?’ Because there’s a lot of gremlins that pop out in that process. To do that, you have to learn a lot.”

Trial and error is inevitable with new technology, he said, so he’s not expecting the first test articles to perform like the final product. “These early field tests, we’re not expecting them to hit the end operational objectives right away,” Estep said. “Some of these I would expect to take several iterative cycles” over months or years.

He emphasized, “we expect to have some pretty notable outcomes even in 2025.”