Artificial intelligence AI research of robot and cyborg development for future of people living. Digital data mining and machine learning technology design for computer brain communication. (Getty images)

WASHINGTON — Despite dire predictions that generative AI like ChatGPT and Sora cloud flood the internet with disinformation and deepfake videos, the new AI tools have been a disappointment for propagandists to this point. That’s the latest word from the general manager of the Microsoft Threat Analysis Center (MTAC), Clint Watts, a former Army officer and FBI agent who’s advised US Central and Special Operations Commands.

In fact, Watts told the Billington Cybersecurity Summit on Wednesday, Russian propagandists have largely abandoned their early experiments with genAI and fallen back on tried-and-true techniques that rely on humans to generate the deceptions, with AI mostly assisting on the margins.

MTAC focuses on nation-state actors, who are much more likely than individual hackers or hacktivist collectives to have access to the immense computing power required to run generative AI. With the US election campaigns gearing up, “it’s the busy season,” Watts said. “We’ve been tracking every time we see a nation state uses AI in some form for internet activity, [and] over the last 14 months, we’ve logged hundreds of instances.”

The lesson so far: AI quantity is no substitute for human quality. With genAI, “you can make more of everything — misinformation, disinformation — but it doesn’t mean it’ll be very good,” Watts told the conference. “The Russians have gone back the other way and just go with their greatest hits” — labor-intensive propaganda techniques honed over decades — “and it works.”

“The Russian actors that we’ve seen, all of them, have tried deepfakes and they moved back to bread and butter, small video manipulations,” Watts told the Billington conference.

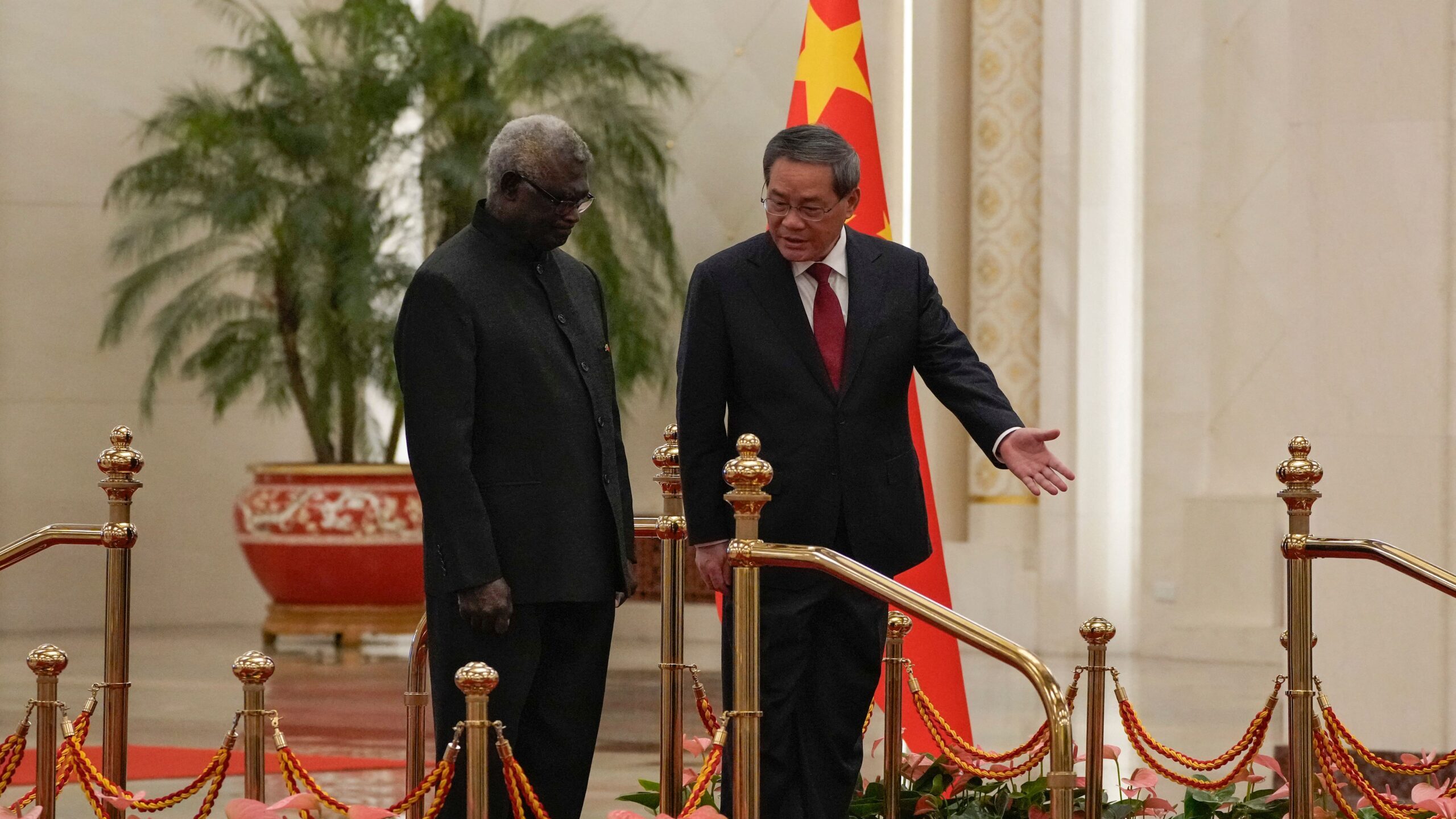

By contrast, recent MCAT reports emphasize Chinese disinformation campaigns have made much heavier use of deepfakes, albeit not very successful ones. That includes profoundly uncanny AI “news anchors” delivering anti-Taiwan-independence messages ahead of the island’s democratic elections, and faked audio of a Taiwanese political leader endorsing a rival candidate, which was quickly detected and taken down. As one MCAT report notes, China doubling down on deepfake video and audio “is where it diverges from Russia.”

Part of the difference is that China has both a much stronger homegrown AI industry and a much smaller supply of well-traveled operatives who’ve personally visited the West, can speak its languages, and understand its pop-cultural nuances.

“For China, they always struggle with cultural context,” Watts said. “They’re just constantly confused. “They don’t have as much experience overseas as the Russians do” — but they have more AI tools available to try to compensate.

That said, he went on, the most effective AI tech is often the most modest. “The most overlooked and valuable piece of Large Language Models is just producing more content in a foreign language,” he said. That content is usually text, he added, or less often AI-generated voiceovers: “Video is tough.”

“Everyone has tried video to some degree but it doesn’t work exactly, because the cultural context part that you get from [AI] text hasn’t made it into [AI] video yet,” he said. Indeed, entirely AI-generated facial expressions and body language often look not just wrong for a given culture, but altogether inhuman, a phenomenon known as the uncanny valley.

Even with the latest video-generation AI such as Sora, “the technology is mostly not quite there,” Watts said. “It’s much easier to do an enhancement to a video than to make a whole AI-generated video. So it’s small fakes that tend to work better, and they are also cost-efficient.”

“Small” can really mean small, here. One recent MTAC report gave examples such as superimposing a real news agency’s logo over a propaganda video to add an air of authenticity. More ambitious efforts tend to rely on AI-generated voices, which are easier to fake than video, such as a Russian genAI imitation of Tom Cruise narrating a propaganda “documentary” that denounced the Paris Olympics for banning Russian athletes. Even so, the Russian campaign failed to derail the massive event.

“We jump to the doomsday science fiction — you know, ‘this is deepfakes, it’s going to destroy everyone’s heads and the world will collapse’ and that sort of thing,” said Watts. To date, however, “audiences have been remarkably brilliant about detecting deep fakes,” he said, especially of well-known public figures. “The more you watch somebody, the more you realize a fake isn’t quite right,” he said, “whether it’s Putin or Zelensky or any of the candidates in the election.”

GenAI’s shortcomings go beyond video, however. “Creativity is the weakness of the LLM from a messaging standpoint,” Watts told the conference. “The narratives that still stick, or the most brilliant things that you’ll see a perpetrator come up with. … I’ve never seen an AI come up with one yet.”