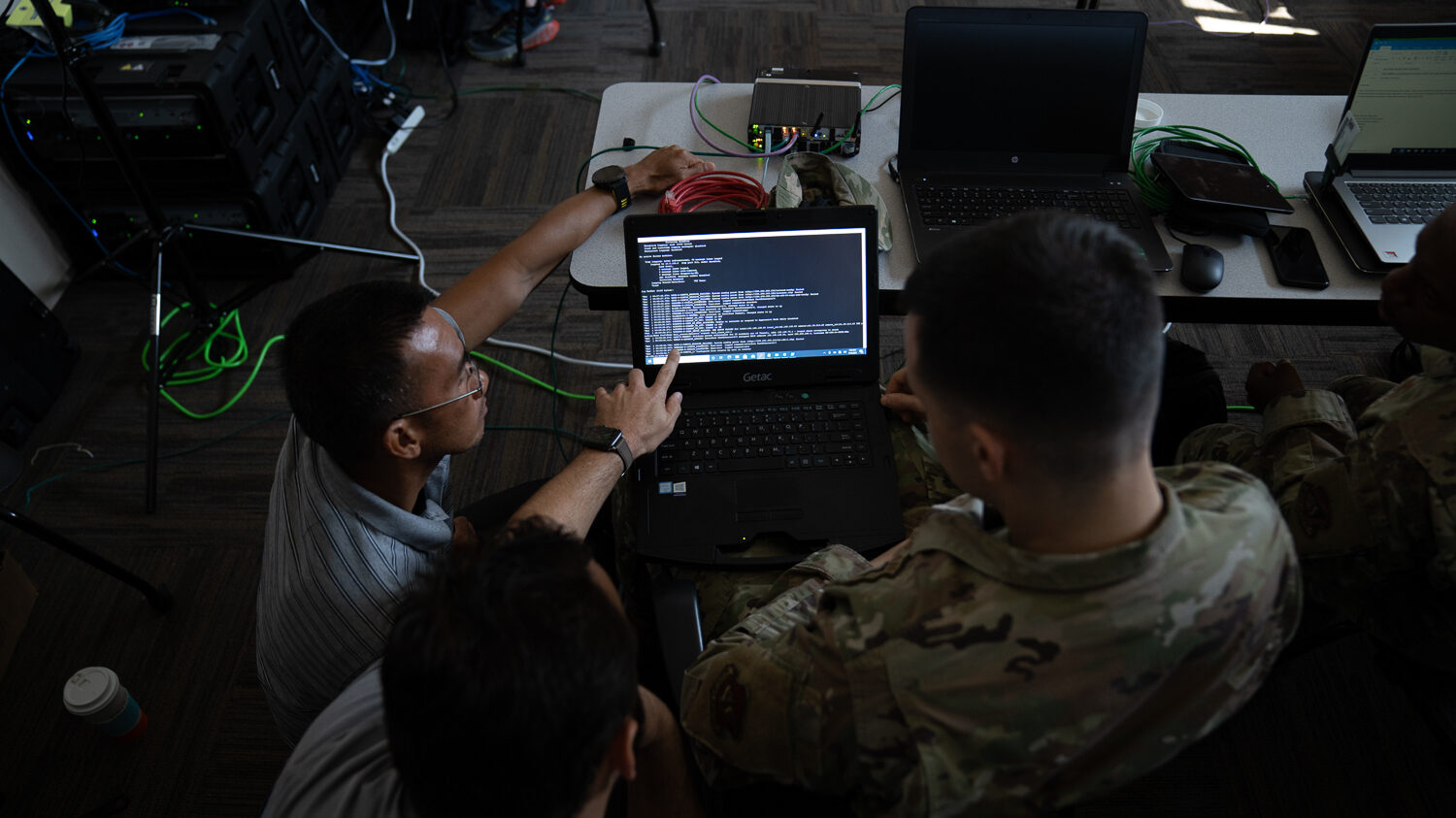

U.S. Army Soldiers, assigned to the 6th Squadron, 8th Cavalry Regiment, and the Artificial Intelligence Integration Center, conduct drone test flights and software troubleshooting during Allied Spirit 24 at the Hohenfels Training Area, Joint Multinational Readiness Center, Germany, March 6, 2024. (U.S. Army photo by Micah Wilson)

WASHINGTON — As the Army moves to modernize the way that it buys software, there’s an abundance of devils in the details. Two senior officials recently said the service is working to streamline the process and promises to work more closely with industry, especially those from non-traditional defense firms — but critics argue the rhetoric of reform isn’t yet matching what the Army is actually doing.

“I fundamentally understand that the business model is different for the non-traditional [companies],” said Leo Garciga, the Army CIO, when the issue came up Tuesday during Q&A at the AFCEA TechNet Augusta conference. “[We’re] trying to work through this right now.”

Industry’s objections involve custom development of bespoke software for the Army, paid for using a unique, Pentagon-prescribed system of cost accounting, instead of just buying commercial software off the shelf for the sticker price. These cost-accounting practices are old hat for traditional defense contractors. But, industry experts argue, they are so unfamiliar, complex, and difficult to implement for commercial software companies that they might effectively deter the most innovative tech firms from competing.

“There are a lot of things we’re looking at [and] feedback from industry is critical,” said Jennifer Swanson, the Army’s software acquisition chief, at AFCEA, less than an hour after Garciga’s remarks. “We are working very closely with all different types of companies. … We want to make sure that non-traditional smalls, as well as larges and others, have opportunity to compete for the work. That’s how we get the best product to the soldier.”

Those Army leaders are saying the right things, three critics told us, but the actual acquisition language is, right now, very different. At issue are recent Army documents intended to reform procurement:

the March Army Directive 2024-04 [PDF] on “Enabling Modern Software Development & Acquisition Practices”;

a Request For Information (RFI), issued in May and updated in August, soliciting industry input on a new multi-vendor mega-contract for software procurement, officially known as the MSD MA IDIQ (Multiple Award Indefinite Quantity Indefinite Delivery Contract for Modern Software Development)

“It seems that many of the right things were said publicly regarding the aversion to custom development projects and re-inventing the wheel,” said Warren Katz, a software entrepreneur and investor, who is chairman of the board at the Alliance for Commercial Technology in Government. “However, those sentiments do not seem to have translated into the RFI and Directive documents.”

Another industry official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said that the RFI suggested the Army was “heading in a better direction to allow more industry participants to bid,” but said Army policy still favors cost-plus contracts rather than firm fixed-cost ones. “This gives non-traditional industry participants pause,” they said.

AEI senior fellow Bill Greenwalt, who helped write acquisition reforms into law in his days a congressional staffer, put it more bluntly. “These people have lost their minds and have spent too long in Army contracting to understand how the real world works,” he said. “There is no one on the globe that does software development on a cost-plus basis.”

The Cost-Plus Problem

The specific crux of contention is a Pentagon-specific practice called cost-plus contracting, which industry critics say is starkly different from the firm fixed-price model preferred by commercial software companies.

The cost-plus model isn’t totally alien to the private sector: There are plenty of businesses, from home repair specialists to law offices, where a client pays for a contractors’ time and materials, plus a percentage to cover overhead and profit. Military development programs — for everything from stealth jets to software — are particularly tricky to price out in advance, because they’re so prone to unforeseen technical programs that cauase them to overrrun their budgets.

The hard part is determining what is and isn’t a legitimate “cost” to be reimbursed. To do that, the Defense Department imposes a strict, complex, and unique system of cost accounting that requires companies to track, among other things, hours worked by employees of various government-defined grades.

This works, sort of, for companies building traditional weapons systems like tanks, warships, and planes: Those are physical objects built by employees in formally classified trades — welders, fitters, electricians, and many more — who are generally paid by the hour.

But, industry sources explained, systems to track labor costs for cost-plus contracts this way can’t cope with the chaos of modern software development. Some of the most productive coders have little formal training and work wildly irregular hours, depending on the needs of the project. Asking these mavericks to track their billable hours, like lawyers, is like trying to leash lightning: impractical, expensive to even try, and likely to get someone badly burnt.

Army leaders say they’ve heard the criticism and are rolling back at least some of the cost-accounting requirements.

“We put out a draft RFI on Friday [and] inadvertently included labor categories that have all of the education requirements and things that we’ve always used that don’t really make any sense anymore,” Swanson said at AFCEA. “We’re going to get rid of that.”

On the other hand, Swanson said, that doesn’t mean the Army should give up on cost-plus contracting altogether and rely exclusively on firm fixed-price contracting for all software.

“I think there’s been confusion with the software directive,” she said. “When we’re buying straight up commercial software, it’s firm fixed-price. There’s no other way to buy that that would make any sense.”

However, she went on, “where firm fixed-price doesn’t make sense is when we are developing software, [because] requirements are going to change. … That becomes a big risk.”

But that’s a risk the Army doesn’t need to take, counter the critics. The commercial market already has software for virtually every occasion that the government can buy for the firm-fixed price on the sticker, they say, without needing to pay extra to build bespoke solutions — let alone to do so using cost-plus contracts.

“The $5 trillion software industry has over 30,000 SaaS [Software as a Service] companies, an estimated 500,000 IT and software services companies, and an estimated 2.8 trillion lines of code written to date,” Katz said. “The likelihood that much of the Army’s needs can be met by existing commercial products is exceedingly high.”