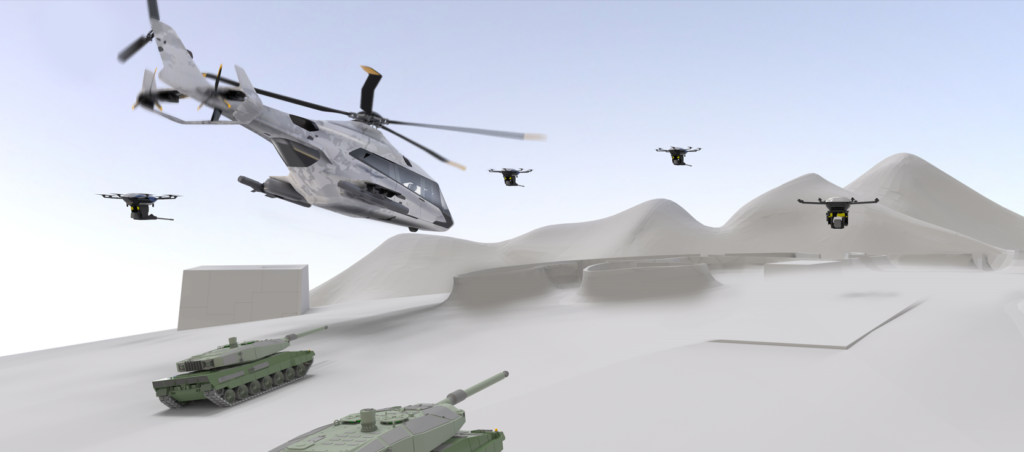

BAE concept art for what its future autonomous collaborative platforms could look like. (BAE)

WARTON, United Kingdom — BAE Systems hasn’t finalized its sixth-generation fighter, but company execs are already talking about a “seventh-generation” combat air platform — even though they say that term will probably be out of date by the time it rolls around.

Discussing the future of combat air at a media roundtable on May 14 at its manufacturing and assembly site in Warton, Lancashire, BAE Systems’ Combat Air Strategy Director, Mike Baulkwill said he “didn’t know where 7G aircraft development is heading,” but added, “We need to lose the generational name because aircraft are going to be evolving all the time.”

“There will be a baseline architecture which could be developed quickly and in an agile manner,” Baulkwill said, but generation-after-next aircraft will be “forever changing” through software updates and spiral developments.

Baulkwill’s sentiments were supported by BAE’s Jonny Moreton, partnership director and military advisor for the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), who agreed “generational nomenclature” will disappear in the future. “Aircraft will be reliant on software and mission data to respond to emerging threats,” he said.

BAE Systems and its UK industry partners Leonardo, MBDA and Rolls-Royce are developing a sixth-gen combat air capability through the UK’s FCAS effort, which is nested under the trilateral Global Combat Air Program (GCAP) with Italy and Japan, due to enter service in 2035.

The comments came as BAE presented its “Combat Air Continuum” concept — essentially laying out how the company sees the next 25 years of airpower, and hence an indication of where the company will look to invest its R&D efforts going forward.

RELATED: FCAS? SCAF? Tempest? Explaining Europe’s sixth-generation fighter efforts

In the near term is what the company calls the “second epoch,” which will see a mix of fifth and sixth-gen platforms, with both augmented by what they call autonomous collaborative platforms (ACPs), aka loyal wingman drones. Those systems would help extend the lifespan of older jets like the Eurofighter Typhoon.

Referring to a future force mix of fourth, fifth and sixth-gen combat air platforms, Baulkwill suggested a “golf bag approach” which would enable air forces to operate a flexible portfolio capable of addressing threats.

“Most of our aircraft have gone out far beyond where they were designed for,” he said before suggesting how fourth-gen air frames like the company’s own Typhoon aircraft could be used to provide combat mass and to “protect” high-value sixth-gen fighters because the Royal Air Force (RAF) will not want them flying “all the time.”

According to Moreton, such a force mix could be “relatively enduring for the next 15 to 25 years”- something he believes will enable air forces to “demonstrate presence with lethal [fourth-gen] effects.”

Then a “third epoch” will roll out between 2046 and 2055, which will see western air forces operating “full 6G capabilities, augmented by autonomous combat aircraft taking diverse roles [and] potentially 7G fighter aircraft programs being developed [with] potential for wider collaboration and consolidation,” according to a company presentation.

Baulkwill also said there will always be a need for “combat mass,” particularly when it comes to homeland defense applications: “The Royal Air Force is working hard right now and this is a concept for the Ministry of Defense [MoD] to decide upon because it does look like it’s spread quite thin.”

But he also warned the MoD will need to strike a balance between technology, capability, cost and mass although he conceded combat mass will be heavily dependent upon availability.

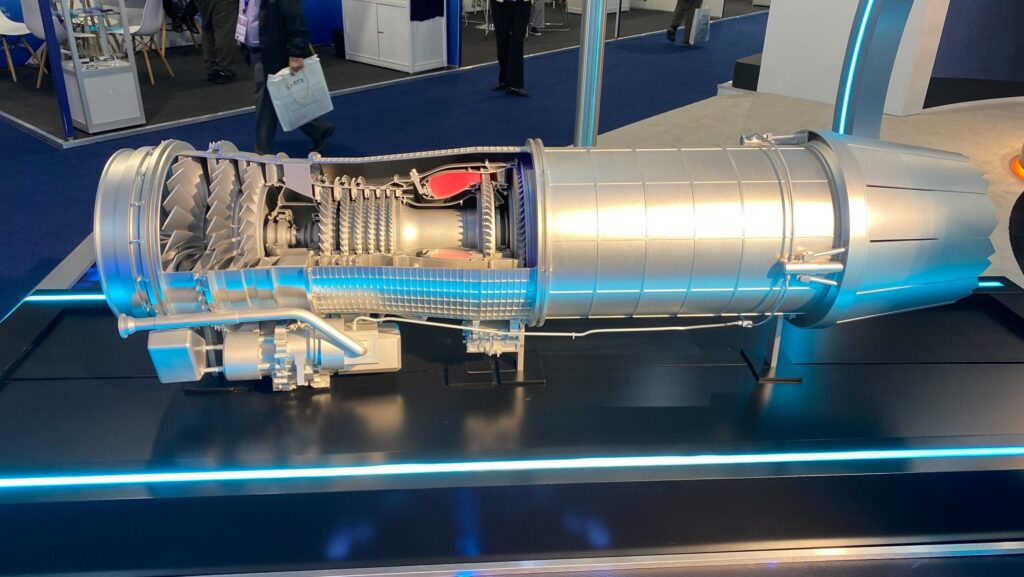

BAE also presented its “latest thinking” on what its attritable ACP project might look like, though company officials suggested a scale model presented at Warton may not necessarily reflect a final design.

According to company literature, the ACP could be made available in land or maritime variants, featuring a pair of internal payload bays and containerized storage space capable of carrying payloads to support electronic attack; precision air-to-surface munitions; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; air-to-air and air-to-surface logistics.

“At some point there will be a decision when we have to downselect an air frame and we have to find that point,” Neil Appleton, CEO of BAE subsidiary Malloy Aeronautics, said before describing the ACP as “incorporating goal-based autonomy that is capable of independent or synchronized action with combat air.”

Of course, the last four years have shown that procurement plans can fall apart quickly if the supply chain and workforce isn’t there. The execs, when pressed, acknowledged that will likely remain a challenge going forward, with Baulkwill suggesting that if the UK was drawn into a conflict near-term, the biggest concern will be sourcing of materials to increase production and support capacity for Typhoon.

Describing ongoing discussion within the MoD, he said, “There is more to do before the UK can put subsystems on the shelf and manufacture aircraft at pace. But it does have the skill sets in right areas with BAE, Leonardo UK, MBDA and Rolls Royce.”

He also suggested there were lessons in combat air to be derived from the ongoing war in Ukraine but warned “you can never be sure that is what the next fight is going to be [like].”

![The sights from the 2024 Farnborough Airshow [PHOTOS]](https://centurionpartnersgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IMG_8722-scaled-e1721930652747-1024x577-hZjwVb-500x383.jpeg)