The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) Headquarters. The NRO designs, builds and operates spy satellites for the CIA and Department of Defense. (Photo by Greg Mathieson/Mai/Getty Images)

WASHINGTON — The Space Force for months has been dragging its feet to fulfill the longstanding agreement between the Department of the Air Force and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) on the assignment of military personnel to the spy satellite agency, according to a handful of government and industry sources — resulting in a shot across the service’s bow by lawmakers in the recently passed fiscal 2025 Intelligence Authorization Act.

“You know how this stuff works on the Hill: When stuff shows up in bill language, it usually indicates longer discussions behind the scenes. For it to finally end up in a bill, it means that they haven’t had satisfactory meetings, or no answers to questions,” one congressional staffer explained.

In a joint statement accompanying the FY25 intelligence policy bill, the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI), detail the negative repercussions for both the NRO and the Space Force from a lack of service support.

“The NRO is negatively affected — and its ability to meet warfighter requirements diminished — when the United States Space Force does not assign Guardians to the NRO at a rate that meets the NRO requirements; … The NRO and Space Force are negatively affected by the Space Force’s uneven emphasis on developing space operators without similar emphasis on developing Guardians with space acquisition and engineering expertise,” the statement reads.

And in an attempt to push the Space Force to act, the statement mandates that the Director of National Intelligence provide both the Intelligence and Armed Services committees with updates on “the status of the Department of Defense fulfilling its commitment to assign uniformed personnel to the NRO.”

The Space Force did not respond by press time to a request for comment.

Guardians Comprise Bulk Of NRO Uniformed Staff

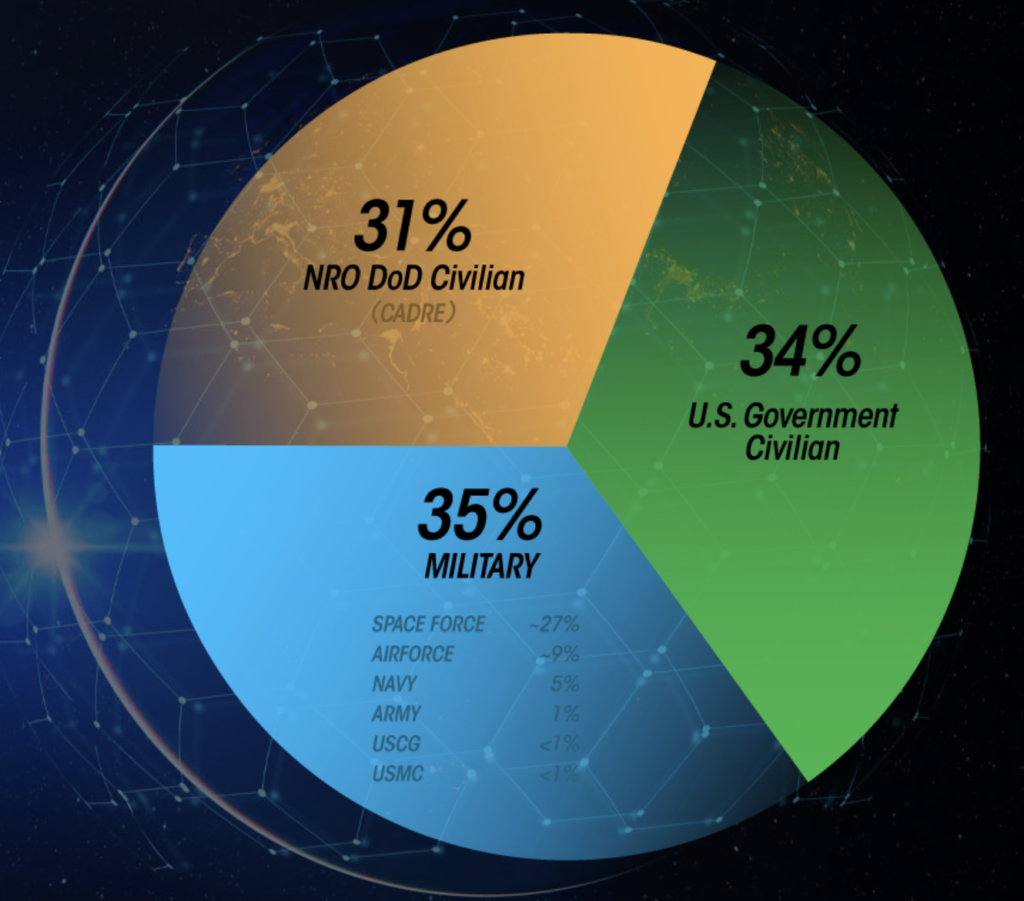

The issue is not trivial for the NRO, in that military personnel with space expertise previously from the Air Force and now from the Space Force traditionally have made up about one-third of the NRO’s staff. An NRO spokesperson explained that there are “agreements in place” between the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and DoD “to manage” Air Force and Space Force “manning requirements” at NRO.

“The NRO in partnership with the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the Service Secretaries routinely monitor and evaluate the best mix of uniformed personnel at the NRO to meet mission needs, as well as the needs of other elements of the DoD,” the spokesperson said. “U.S. Air Force personnel have historically represented the largest portion of the NRO’s workforce. With the establishment of U.S. Space Force in 2019, this distribution has shifted to Guardians representing the largest segment of the NRO’s military workforce.”

According to the spysat agency’s website, the NRO workforce currently numbers about 3,000 with 27 percent provided by the Space Force. The service “is a critical partner to NRO, particularly in space system development, operations, engineering, and acquisition. … [I]t’s important the NRO and U.S. Space Force receive the support necessary to advance our shared mission in space, ultimately safeguarding the U.S.’s national security space advantage,” the spokesperson said.

However, sources were mum on exactly how many people, if any, the Space Force has offered for this fiscal year.

Personnel seconded from the military services make up 35 percent of NRO’s approximately 3,000-strong workforce, with the Space Force alone normally accounting for about 27 percent. (Graphic: NRO)

Space Force: Small Size, Big Portfolio

There are several factors at play in the service’s reluctance to provide Guardians to support the NRO’s mission of acquiring and operating intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance satellites, according to experts, current and former government officials, and Hill staff.

First and foremost is that Chief of Space Operations Gen. Chance Saltzman is struggling to find enough personnel from his relatively small workforce — slated to hit just over 15,000 this year; 9,800 uniformed and 5,200 civilians — to fulfil growing service missions and ensure timely training, as well as support combatant commands, joint force organizations and interagency functions. Saltzman and other top Space Force brass have been advocating for the past year for more Guardians, and more funding for its burgeoning mission profile.

“Currently the Space Force is underfunded, undersized, and without the authorities necessary to consolidate DOD space agencies,” said David Deptula, dean of the the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

But another, according to these sources, is Saltzman’s own lack of interest in acquisition issues and building those skills within Space Force cadres — an issue that already has piqued concern from the House Armed Services Committee. NRO, while operating its own satellite fleets, is largely an acquisition organization.

“This is definitely a blind spot for Salty and the [congressional] statement is surprisingly direct,” said Doug Loverro, former head of Pentagon space policy who remains active as a consultant on Space Force issues.

Finally, there is the fact of the long-running animosity between the Intelligence Community and the Space Force on the boundaries of each side’s authorities, with the Space Force over the past year arguing to take over a number of missions previously considered within the remit of the NRO and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Those turf wars may get worse before they get better as Space Force advocates see opportunities with the incoming Trump administration to push for expanding the service’s mission parameters even further. For example, there have been renewed calls among some service advocates for the Space Force to swallow NRO whole.

“Of course, this issue could be solved by placing the NRO into the Space Force to comply with the original rationale for standing up the Space Force — the need to consolidate the nation’s fragmented multitude of space organizations into one organization,” Deptula said.

It is unclear, however, what affect the HPSCI-SSCI language will actually have in resolving the staffing issue, given that neither committee has direct oversight or budgetary control of DoD and the military services. And while HASC leaders are frustrated with the service with regard to the acquisition issue, neither committee has taken action on the question of NRO support — although a number of sources said staffers clearly are keeping an eye on the problem.

One possible solution the Armed Services committees could put forward, according to a couple of sources, is to put language in the annual National Defense Authorization Act mandating that the Pentagon consider a more equitable sharing of the NRO support burden among the services. Currently the Army, Air Force and Navy provide only single-digit percentages of the spysat agency’s workforce, and each of those services maintain space experts within their cadres.

“That makes great sense,” Deptula said.

Meanwhile, NRO is having conversations among its various partners on the issue of keeping its desks full.

“NRO maintains a strong relationship with all of our partners including the U.S. Space Force and we have ongoing discussions to ensure agreed upon staffing levels are met,” the spokesperson said.