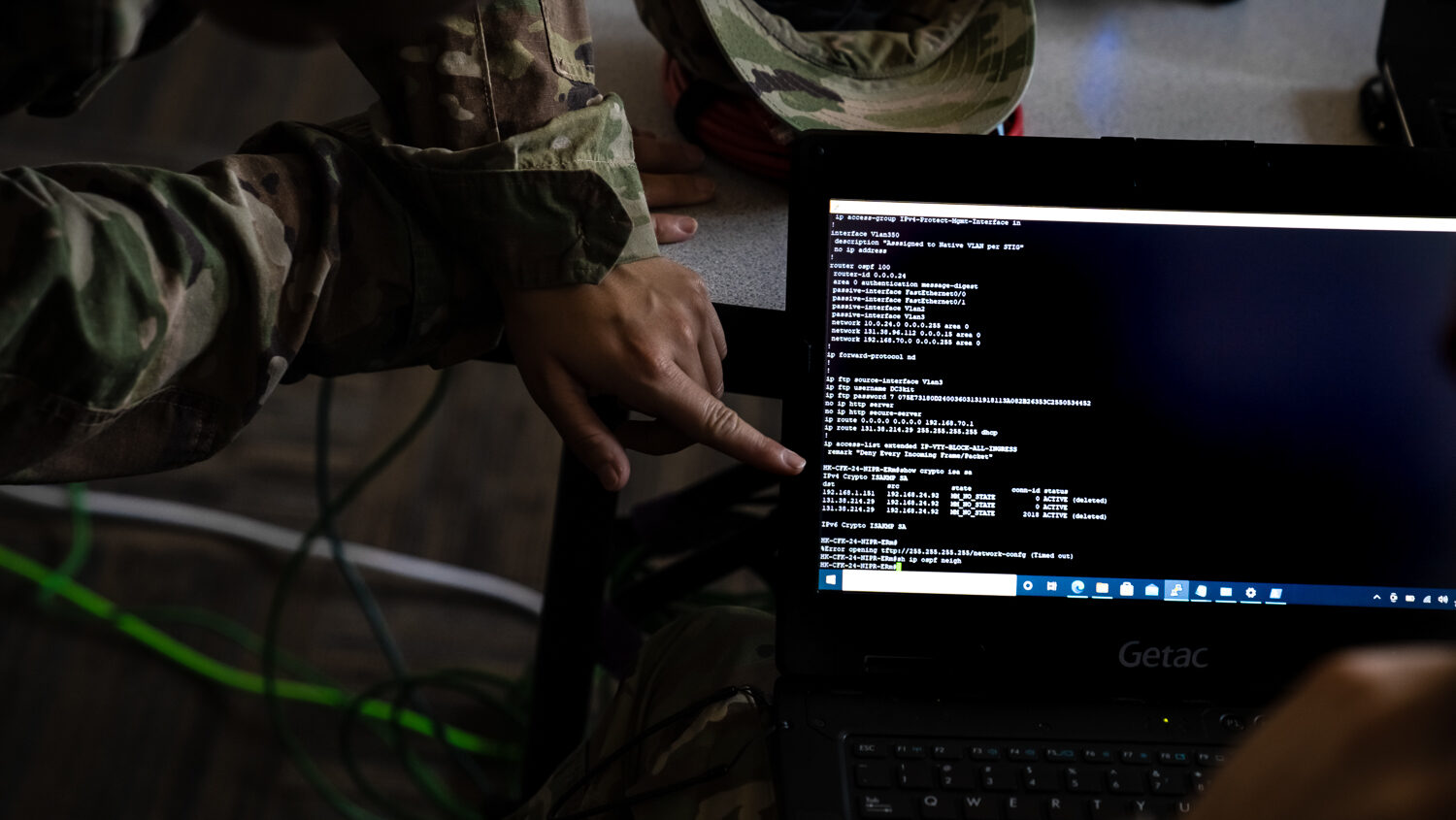

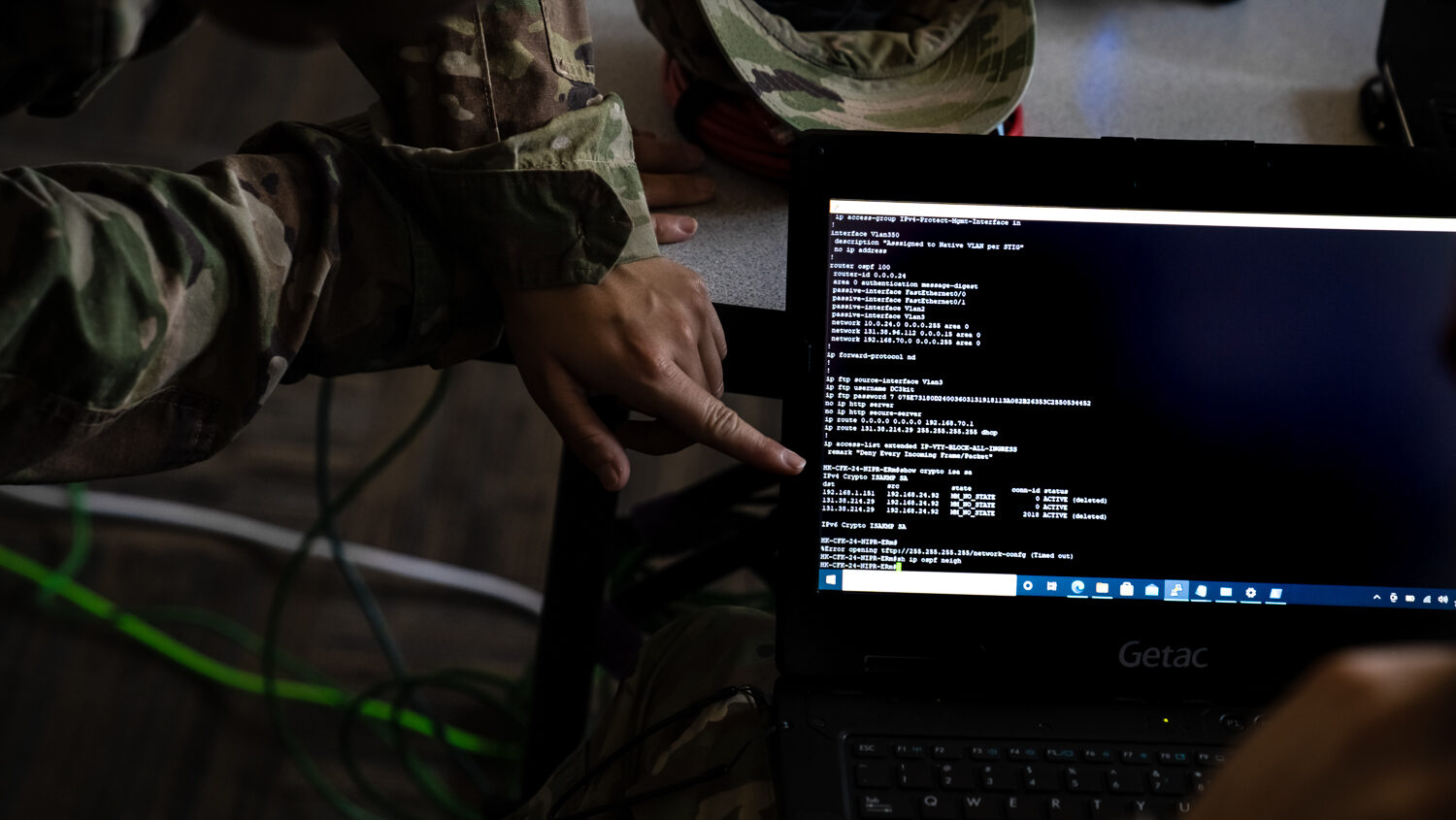

Members of the 56th Air and Space Communications Squadron at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam operate cyber systems using a Enhanced communications flyaway kit during the Global Information Dominance Experiment 3 and Architect Demonstration Evaluation 5 at Alpena Combat Readiness Training Center, Alpena, Michigan, July, 12, 2021. (U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Amy Picard)

WASHINGTON — This year saw major progress in the Pentagon’s years-long push to harness artificial intelligence — not for drones or “killer robots,” but for software tools that help staff officers bring some order to the chaos of modern conflict.

From the intelligence analysis algorithms of Project Maven, the seven-year-old granddaddy of military AI tools, to the data-sharing systems collectively known as CJADC2, 2024 has seen significant expansion in both capabilities and the number of people using them for real-world operations.

These unglamorous utilities matter, because the ultimate weapon is often not a weapon at all. Prussia united Germany in the 1800s in large part thanks to the superior organizational skills of its General Staff. The Nazi Panzers in 1940 didn’t outgun or outnumber their French opponents, but they had radios to coordinate mobile operations, while the French relied on landlines and signal flags. The Pentagon itself, today a byword for bureaucracy, was built in 16 months to house the massive administrative apparatus essential to running a global war.

Victory, in short, doesn’t go to the side with the shiniest toys, but to the organization that manages the digital grunt work most efficiently. Here’s how the Pentagon applied AI to military command and control in 2024:

[This article is one of many in a series in which Breaking Defense reporters look back on the most significant (and entertaining) news stories of 2024 and look forward to what 2025 may hold.]

1. First version of all-service battle network is ‘real and ready now’: Hicks

In the 21at century paper files, voice calls, and human staff are no longer enough to stay on top of fast-moving events on land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace. The need to share data, intelligence, and orders rapidly across those five “domains” drove the Department to Defense to try to develop an AI-powered system of Combined Joint All-Domain Command & Control. While “CJADC2” is still a nascent capability with many well-informed skeptics, the last 12 months saw the first pieces of it move from experiments to real-world operations.

In February, Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks publicly announced an initial version of CJADC2 — the “Minimum Viable Capability,” a spin on the software industry term of “Minimum Viable Product.” (The MVC had actually been certified as ready in December 2023, after months of urgent work, but it wasn’t announced for another three months). This version was focused on sharing information among the military’s 11 four-star operational headquarters, the Combatant Commands — but the military immediately began expanding it.

2. ‘Who should shoot who?’: INDOPACOM getting ‘combat representative’ JFN this year

One of the most sought-after CJADC2 capabilities is, in essence, fire control. The US military has a large and growing arsenal of long-range weapons, from Air Force stealth bombers to Navy guided-missile subs and destroyers to new Army truck-mounted missile launchers.

Traditional processes for figuring out which target is best attacked with which weapon, like the daily Air Tasking Order (ATO), require big staffs and lots of time, making it difficult to adjust to new intelligence or enemy maneuvers. And the more drones, satellites, and other sensors are feeding data in the front end of the process, the more overwhelmed the human middlemen become.

So much of the CJADC2 work this year has focused on something called the Joint Fires Network. JFN doesn’t take human fingers off the trigger, but it automates the process of suggesting “who should shoot who” for the human commanders to sign off on (or amend) and for human troops to execute. While not yet operational, a prototype of JFN impressed officials during June’s Valiant Shield wargames in the Pacific and a “Version 1.0” is expected to enter service by early 2025.

3. Decentralizing battle data: CDAO, Anduril open tactical ‘mesh’ to third-party developers

The CJADC2 Minimum Viable Capability and Joint Fires Network looked at warfare from the top down, but the American military, at its best, is infamously bottom-up and inventive. Besides, big HQs are big targets, vulnerable not only to direct attack but to signal jamming or network hacks that cut off their communications.

So the CJADC2 effort includes a tactical dimension. For frontline units to share data directly, rather than wait for updates to come down from higher headquarters, their digital systems have to understand each other. That turns out to be technically complex, especially as the military deploys more and more sensors built by more and more contractors.

So, after several years of quiet experimentation, this month the Pentagon publicly announced a $100 million, three-year contract with Anduril for large-scale deployment of the company’s Lattice Mesh. The critical ingredient: a set of translation algorithms that lets a unit with Lattice make sense of sensor feeds from over a hundred different systems, without having to wait for a central hub to do the data processing.

4. Open DAGIR: DoD plans July industry day, experiments for new CJADC2 command apps

A recurring theme in the evolution of CJADC2 is that it is not one thing, but rather dozens of different applications for different purposes, all (in theory) compatible and knit together. Such a “federated” approach to building military technology, however, is at odds with traditional Pentagon procurement practices, which tend to create mega-projects run by a single prime contractor.

Historically, tech built by different vendors tends to use incompatible standards and protocols that make it difficult or impossible to share data. Conversely, any individual system may suffer “vendor lock,” where only the original contractor has the intellectual property required to make it work, locking out potential competitors. The Pentagon, naturally, would prefer CJADC2 work more like Lego, with any piece able to connect to each other and everything easy to replace or rearrange as needed.

To make this work, in May the Pentagon’s Chief Digital and AI Office, the lead agency on CJADC2 and a host of other high-tech projects, rolled out a new way of designing both software systems and the contracts to build them, starting with the Maven intelligence-analysis AI. Known as Open DAGIR, the acquisition construct decouples different elements of a project so they can be built by different contractors and yet still work smoothly together.

5. Empowered edge versus the centralization trap: Who will wield AI better, the US or China?

The ultimate test of any military technology is how well it works in combat, a lethally unforgiving environment. And while artificial intelligence can replace human brainpower for an increasing number of functions, war remains a profoundly human undertaking, where human beings still make the big decisions and do the dying. So how well technology performs depends, in large part, on how humans choose to use it.

For the US, there is cause for cautious optimism here. American military culture, like the civilian society from which it recruits, historically favors initiative and improvisation — in ways its authoritarian adversaries generally don’t. And while Industrial Age machinery lent itself to efficiencies of scale and central planning, Information Age networks have great potential to empower the individual on the ground. The challenge for CJADC2 is to unleash that potential.