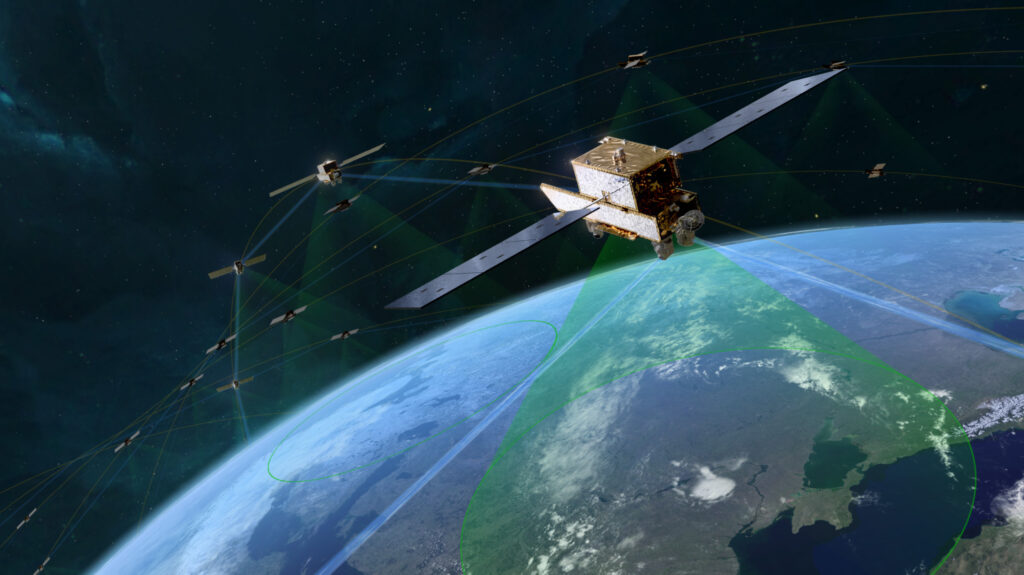

The Space Development Agency’s Tranche 2 Transport Layer constellation is designed to provide high volume, low latency data communications around the globe. (Artist’s view: Northrop Grumman)

WASHINGTON — While citing the Space Development Agency’s progress so far in creating a novel acquisition model, a new study by The Aerospace Corporation cautions that other defense agencies may not be able to follow in its footsteps — further noting that the agency has yet to clear some challenges of its own, including the need to scale up its architecture and prove its success.

“SDA is creating a model for rapid acquisition with distinct characteristics that have contributed to its early progress. Yet analysis of SDA’s approach also indicates that other defense acquisition organizations will face challenges adopting the SDA model for their programs,” states the study, “The Space Development Agency and the Future of Defense Space Acquisitions,” released today.

“Further, SDA is likely to face its own challenges sustaining its model. Congress and DOD leadership have been supportive of the agency and have given it tremendous budgetary and acquisition flexibility. Whether SDA continues to receive flexibility may depend on its operational success as it pursues quantities and time frames never before achieved in defense space acquisition,” it adds.

While author Andrew Berglund gives SDA full kudos for its “impressive speed” so far in concluding development contracts and fielding its first satellites, he also warns that those advocating the agency’s approach as the way for all Defense Department acquisitions in the future may want to curb their enthusiasm given the early stage of the agency’s work.

“Even though it has not yet demonstrated its systems’ capabilities at scale, SDA has been touted for providing an acquisition model that other organizations should adopt. However, the precise features and mechanisms of SDA’s acquisition approach have not been comprehensively studied, including whether it is exportable to other organizations,” Bergman writes.

One potential problem for proliferating SDA’s model, the study points out, is the “distinct” nature of the agency’s approach, including its “structure, culture and process.”

The study argues that many other defense acquisition organizations simply may not be able to mimic SDA’s structure, which was built from the ground up based on the concept of a resilient, proliferated architecture and then finding capabilities that would benefit from that approach — rather than the more common methodology of building a development program based on the need for filling a particular capability gap. In other words, not all critical space-based capabilities may require, or even benefit from, the use of many small satellites built largely using commercially available subsystems.

Nor do many other organizations have the same freedom Congress has granted SDA to play a bit fast and loose with the rules and regulations governing DoD’s overarching acquisition process — such as being exempted from the Joint Capabilities Integration & Development System (JCIDS) for setting military requirements.

“[A] structural characteristic of SDA’s model is that it is designed to build and support a space architecture made up of many satellites that are regularly replaced over time. This provides notable benefits, including more predictable, stable funding and the ability to defer requirements to future efforts. In contrast, most defense acquisition organizations, for which each acquisition is a stand-alone effort, operate with less certainty and greater constraints,” the study explains.

Perhaps more importantly, the study points out that SDA is in the early stages of deploying its architecture.

At the moment, SDA has only 28 “Tranche 0” satellites in low Earth orbit as part of its Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, all of which are technology demonstrators.

Thus, the study argues that the agency has yet to fully prove either that its conceptual mesh networks actually work, or that it can sustain the every-two-year spiral development approach and its constant competition model that requires a robust industrial base. Indeed, it adds, SDA still has non-trivial obstacles to hurdle to do so.

“SDA is in a critical period to show proof of its early promise, with near-term plans to demonstrate capabilities using satellites already on orbit and to greatly increase its launch tempo for follow-on satellites. The agency is likely to encounter several obstacles fielding and then maintaining its architecture, including sustaining a competitive industrial base and scaling its networking capabilities,” the study asserts.

“The success of the SDA model, as well as the organization’s ability to continue operating with the flexibility that has enabled its early progress, will depend on SDA’s ability to navigate these challenges,” it sums up.

SDA did not respond by press time to a request for comment.